BRICS Without Mortar

Despite its recent expansion, the BRICS ‘alliance’ is nothing more than vaporware. Claims of the death of the American-led world order have been greatly exaggerated.

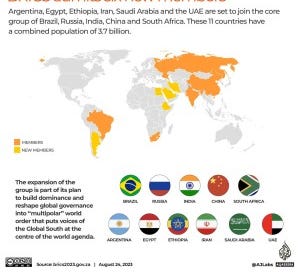

In geopolitical commentary circles, much has been made of the recent expansion of the Global South-centered multilateral association known as BRICS. This grouping of developing world nations is named after its early members – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – and has long been touted as the future pivot of geopolitics, economics, and world organization, displacing the regnant Western-led order. Now that the loose partnership has grown beyond its acronymic members to include Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Argentina, the usual skeptics and opponents of the postwar system – isolationists, the horseshoe of far-right and far-left, self-proclaimed ‘anti-imperialists’ (merely anti-American), useful idiots – have gone into overdrive.

BRICS has been lauded as a full-on movement against the power of “Global NATO,” meant to proffer a more benign, anti-Western vision to reshuffle the world order. BRICS would be an alternative to the hegemony of American interests in international organizations, creating something akin to a new version of the Cold War Non-Aligned Movement – a group that, in contrast to its branding, served Soviet interests. According to the proponents of this idea, BRICS shows that legacy world institutions – including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization – are not irreplaceable and should be reformed to focus on “equitable, inclusive” outcomes. They point to the many initiatives undertaken by the bloc to compete with the liberal order: a massive submarine cable project, the New Development Bank meant to rival the World Bank/IMF, and a push for de-dollarization of international trade. The addition of new members to the group has produced headlines like “American Power Just Took a Big Hit” (in the New York Times) and claims of a “rebalance” of the world order and the replacement of the US dollar as the global currency by a BRICS-created option.

But are these dire predictions of doom for the world system we so benefit from actually accurate? Will the 21st century be one led by a solid BRICS alliance?

The answer, dear reader, is a resounding no. BRICS, with or without its newest additions, is nothing but vaporware. Its vaunted, West-defeating promise has yet to materialize, despite the myriad attempts to incept it into existence. As of now, it exists only as a vessel for the fevered imaginations of anti-Western pundits and the megalomaniacal ambitions of one Xi Jinping.

The ephemeral, transactional nature of BRICS has been evident from the beginning. The term itself, redolent of the broader idea of a growing share of global power and prosperity moving to the developing world, preceded the first summit of the initial ‘founders’ by nearly a decade. The acronym was coined by Goldman Sachs Asset Management chief Jim O’Neill in 2001, when he wrote about the investment potential of the BRIC countries and predicted a future world economy powered by them. Of course, Goldman was ready and willing to be the conduit for that investment – and take a nice vig off the top. Ironically enough, the Great Hope of the anti-West set was created by an American investment bank in pursuit of profits that same anti-West cadre would likely deem “extractive” or “imperialist.” (As an aside, it is quite humorous that this supposed alternative to the Americentric world system goes by an English-language acronym created by an American corporation. So much for opposing hegemony!)

The whole idea behind this group – again, a purely economic one at its conception – is itself suspect. The claim that large emerging economies will inevitably displace the Western order, as exemplified by the G7 nations[1], is deeply flawed and has not been borne out by the evidence. BRICS has been preordained a success story in the business community. But this couldn’t be further from the truth, despite it being rammed down the gullets of students (including myself) for going on 20 years now. First off, the developing world has been the ‘future’ for most of the postwar period, but that would be news to the present. The developed economies of the G7 have had their ups and downs over the past decades, but they are still the world’s best when it comes to prosperity, innovation, and emerging technologies. The dynamism and entrepreneurial spirit of the American economy remains unparalleled, while Europe’s wealth has created one of the planet’s largest commercial markets (and Earth’s most stringent regulatory regime).

Developing economies have taken up many of the cast-off industries formerly dominated by the G7 – particularly manufacturing of consumer goods – while the customer base has largely remained Western. When it comes to the most explosive developing economies, the BRICS nations have mostly been left behind.[2] The real growth markets in the Global South are centered in Southeast Asia, especially Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. At the same time, some of the BRICS nations, including a few of the new entrants, have been languishing in the doldrums. Geoeconomics is an ever-changing game; the future powers of 20 years ago are no longer considered as such. Any supposed bloc organized around the economic powerhouses of the ‘future’ at a single snapshot in time will age very poorly as the world economy itself evolves. In 2001, when Goldman Sachs conjured BRICS out of thin air, the Internet was a bubble in the midst of bursting and social media was but a glimmer in the eye of teenagers like Mark Zuckerberg. Suffice it to say, a lot has changed in the interim.

Of course, these economic concerns and the ironic origin of the BRICS concept are not dispositive of its ability to undermine Western institutional hegemony. In fact, China is counting on it. The Middle Kingdom is the big dog on the BRICS campus, universally seen as the group’s leader and the most powerful player in the geopolitical game. But China itself has not been immune from the economic challenges that plague many of its BRICS brethren. Its vaunted Belt and Road infrastructure initiative has created significant debt issues in many of its recipient nations, making recouping those investment monies far more difficult. Domestically, construction and real estate have been champion sectors for the Chinese economy – just look at those brand-spanking-new cities they keep building! – but they are rapidly coming a-cropper as global macroeconomic winds shift and interest rates rise. In turn, this makes geopolitical arrangements like BRICS all the more important.

China sees BRICS as just one potential resource to aid in overcoming the American hegemony it so despises, but it is clearly one in which the Chinese government is investing heavily. It was Beijing behind the group’s recent expansion, and Xi Jinping was quite ostentatiously well-treated at the latest summit in South Africa. Doubling down on multinational structures like this allows Beijing to present itself as a paragon of developing world success while hoping that increased economic cooperation will rescue it from its own problems. Unfortunately for Xi and his pals, BRICS will never be the silver bullet they need it to be in shunting aside “Global NATO”; the headwinds are far too severe.

For one, several nations in the expanded BRICS group actively detest one another, making consensus on important geopolitical issues quite problematic. Out of the original members, China and India have engaged in repeated violent border conflicts over the past decade, fighting over territory that has been disputed for nearly a century. This is no minor territorial dispute; the lands in question sit high in the Himalayas and control access to both key mountain passes and the headwaters of some of Asia’s most important rivers. Over just the past few years, dozens of troops have been killed or injured on both sides, in brutal melees using clubs, knives, and other non-firearm weapons. What’s more, India is part of the Quad alliance group – itself, the United States, Japan, and Australia – which is a bloc whose prime, if unstated, purpose is to counter Chinese expansionism in the Indo-Pacific. Likewise, China is close economic and military partners with India’s fiercest rival, Pakistan. Beijing works with Islamabad to build dual-use infrastructure, extract resources, and exercise and train their militaries for joint readiness. Given their mutually exclusive interests, China and India are not exactly on a glide path to friendship.

The new entrants to the BRICS bloc are really no better in terms of intergovernmental comity. Iran and Saudi Arabia (plus the United Arab Emirates on the Saudi side) are mortal enemies that have been vying for regional supremacy for the whole of the 21st century. Despite recent surface-level cooling of tensions between the Sunni and Shia states, the fractures in the relationship run extremely deep. Besides the age-old religious dispute between the two main branches of Islam, the nations themselves have ramped up their conflict kinetically. Iran has attacked Saudi Arabia directly and through its proxies, while the Kingdom has, alongside the UAE, fought Iran’s Houthi patsies in Yemen. The two sides have intervened – surreptitiously and openly – in regional politics throughout the Middle East, all meant to undermine the other’s quest for local hegemony.

In Africa, things are not much better for BRICS. Egypt and Ethiopia, another set of new entrants to the group, have been at each other’s throats over the critical issue of water rights. Both are seeking greater control of the Nile for irrigation, transport, and potable water, but their plans directly clash. If Ethiopia dams the Nile closer to its source, Egypt will suffer. But if Egypt is able to procure the water it seeks from the ancient river, Ethiopia will lose the ability to provide water security for its citizens. In a region as dry as North Africa, this is a truly thorny issue. None of these seemingly intractable conflicts bode well for intra-BRICS consensus.

On top of these major problems, the eleven nations of the expanded BRICS share very little in common politically, geopolitically, economically, or otherwise. Some of its members are autocratic, while others are democracies of varying success. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are straight-up monarchies; Russia, China, Iran, and Egypt are autocracies (some verging on the totalitarian); Brazil, Argentina, Ethiopia, South Africa, and India are more or less democratic societies. The serious differences in political systems impact governmental decision-making and the stability of policy choices. Agreements made between the BRICS nations may not be as durable given these divergences and the potential for popular pressure to alter the political calculus in democratic systems.

Economically, these are all developing nations, but that term encompasses a very broad group of markets. Some nations, like India and Ethiopia, are growing rapidly; others, like Argentina, Brazil, and Russia, are stagnant. Some nations focus on extraction of resources (mostly the petrostates of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Russia), while others are primarily manufacturing-oriented (India and China). This may not seem important for an international alliance – hey, isn’t diversification a good thing? – but it very much is. The policies advocated by nations reliant on different sectors will necessarily diverge. Resource extractors will want high commodity prices, while manufacturers will desire cheaper fuel and raw material inputs. The policies which would achieve those goals are diametrically opposed. So much for joint economic policy!

Geopolitically, BRICS is even more of a bumptious crew. Oddly enough for a purported anti-West partnership, several of the BRICS are militarily aligned with the United States. Egypt, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and India are all close security partners of Washington and are enmeshed within the broader Western military ecosystem. Russia, China, and Iran are inveterate foes of the world order that such military affiliations prop up. Strategic interests do not align whatsoever within BRICS, making any sort of coordinated action all but impossible. Its proponents tout it as a non-strategic grouping, but some of its members (ahem, China) clearly wish it to be the opposite. Russia’s war in Ukraine shows the flaws of this arrangement when it comes to geopolitics. Even though Ukraine itself is not allied with any of the BRICS nations, the Russian invasion has negatively impacted several of them. Places like Egypt and Ethiopia are experiencing civil strife and hunger pangs due to the disruption in the Black Sea grain trade they rely on to feed their impoverished populations. Ukraine was the breadbasket for this part of the world in the pre-war era, but Russian disruption of Black Sea trade has dramatically reduced or entirely eliminated this key source of food. So far, this has not made a dent in the BRICS bloc, but the grain issue is not going anywhere and will only metastasize as the war continues. Surely that’s no help to a budding alternative to “Global NATO.”

Finally, the nations of BRICS are dogged by a plethora of internal issues which make coordinating high-level strategy a Herculean task. These run the gamut from major security challenges to significant economic headwinds, but all are severely problematic for any joint effort across the BRICS bloc. Argentina, for example, is an economic basket case, suffering sky-high inflation and excessive prices for basic goods and services. This is nothing new, but it sure poses problems for the group’s broader economic outlook. As discussed earlier, China is facing its own economic issues, with large-scale failures in critical sectors like infrastructure and construction. Alongside those fiscal problems, the People’s Republic is dealing with demographic concerns that could stymie not only its future growth, but its very ability to exist as a superpower. The draconian and immoral One Child Policy, which was official dogma until 2015 (!), caused a massive oversupply in the number of men as compared to women, largely due to the scourge of sex-selective enforced abortion. This disconnect has caused major social issues, with marriageable men greatly outnumbering their female counterparts.

The security challenges faced by several of the BRICS nations are enormous and will make it extraordinarily difficult to make any real joint policy. Ethiopia is in the midst of a brutal civil war, with hundreds of thousands of internally-displaced persons, significant casualties, and potential ethnic cleansing all happening. Governments that are distracted by such horrors are rarely able to focus their minds externally, much less make a coherent policy with a disparate group of nations. Iran faces similar challenges, with waves of persistent internal protest which are taking much of the regime’s energy away from other tasks. Iran is also subject to punishing Western sanctions, which have worked to constrain and limit its economic options. Even with the Biden administration’s push for sanctions relief, Iran is still suffering serious hardship on the financial front. Russia is in the same boat, having been harshly sanctioned after its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. That war, besides bringing down economic ruin on Moscow, has dragged on for more than a year and looks unlikely to end anytime soon. Russia has taken hundreds of thousands of casualties and lost millions of dollars’ worth of military materiel. The Ukrainian conflict has soaked up much of the Kremlin’s bandwidth, making it a far less potent player in BRICS. In fact, Vladimir Putin was himself unable to attend the group’s recent summit in South Africa due to fears of arrest on human rights and war crimes charges. These problems are not going away anytime soon and will hamper the ability of the BRICS bloc to act as one on important issues.

None of this is to say that the Western order can ignore all of these nations entirely; some still pose a serious danger to the world system – the axis of Iran, Russia, and China, most notably. But the BRICS group as a whole is far too fractious and unwieldy to do anything meaningful in an economic or geopolitical sense. Indeed, America would likely be better off if China focuses more on BRICS than on the tighter, more politically-aligned nations mentioned above. This would ensure that precious energy and time is wasted on vaporware instead of actually working with like-minded nations to undermine the world order. It also segments out some of the other malign actors – Cuba, Venezuela, Syria, North Korea – that could join a smaller Iran-Russia-China axis, laser-focused on attacking American hegemony. BRICS is too big a stage for such international pariahs, which is good news for us.

With strategic diplomacy and the right leaders in the target countries, the US may have the ability to detach some of the BRICS nations from their Chinese entanglement. India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt are already more aligned with the United States than they are with the rival bloc, especially given the military ties between the nations. Given the right circumstances, Brazil and Argentina could be picked up and deposited back into the American column as well. The free nations of the Western Hemisphere are linked by history and politics; we are natural friends if we decide to prioritize those relationships and ground them in our mutual values. We should focus on maintaining and expanding our ties with the BRICS nations – aside from the anti-American hardliners – as long as they are willing to work with us and do not buy wholesale into the Chinese vision of the new world order.

On top of that, American diplomacy should be oriented directly towards the most critical nations for our national and geopolitical interests in the 21st century: our closest friends, the nations of Southeast Asia, and the growing democracies of the Global South. Our ties with the G7 countries and our traditional allies outside of that arrangement (Israel, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia, Mexico) are the pillars of the world order we seek to defend. Southeast Asia is the locus of the Indo-Pacific battleground on which we will contest world supremacy with Beijing, so those nations are crucial to our future success and should be integrated tightly into the American economic and security architecture. Developing countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines are potential bulwarks of a revitalized international order and should be courted assiduously. They serve as the pivot of the 21st century, sitting astride the most important commercial and geopolitical routes of the near-future. It would be diplomatic malpractice to allow them to be subsumed fully into the Chinese orbit. Other growing democracies in the Global South are also potential American allies, including Nigeria, which is the most significant state in sub-Saharan Africa. We should not forgo these broader ties to focus myopically on one region or challenge; the danger posed by the China-Iran-Russia axis is a global one, not a localized threat.[3]

With these actions, America and our allies in the international order can press our advantages and defend our weaknesses from the dagger pointed at the heart of the world system. But one thing we have no need to worry about is the ‘alliance’ known as BRICS. It may look powerful on paper, but in reality, it suffers from a terminal lack of shared interests and ability to act in concert. These BRICS may be solid on their own, but they have no mortar to bind. And that, dear reader, creates a very sketchy foundation.

[1] The G7 consists of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, and Japan.

[2] India is a significant exception, and we will discuss China’s economic status in just a bit.

[3] Although each must be dealt with in its own way and with its own discrete tactical approach, as I wrote for Providence here.