Beware of “Democracy in Danger”

The rhetoric of imminent threats to the political system has been used and abused throughout history to stifle dissent, polarize politics, ostracize opposition, and much, much worse.

Political persuasion has been an art for millennia, going back to the very earliest non-absolutist systems such as ancient Greece and republican Rome. In those days, the targets of persuasion were primarily a socially-homogenous elite oligarchy which controlled politics without real input from the majority of the people. As time went on and these systems evolved (with fits and starts) into their more modern and recognizable forms, bringing more people into the political process, the targets of persuasion broadened. This expansion of the electorate, especially after the democratic revolutions and reforms of the 18th and 19th centuries, helped lead to the simplified messaging, inflammatory rhetoric, and hyperbolized language we are so familiar with today. Perhaps the easiest message by which to persuade voters to your side is the invocation of peril, especially to the political system or “way of life.” Much of the power of this message emanates from the association of the State with the People more broadly; instead of Louis XIV’s formulation “L’état, c’est moi,” we have a more pluralistic – although no more accurate – vision, “Létat, c’est nous.” This binding of People with State makes it possible to expand a narrow political danger to encompass all of society, feeding an attitude of existential menace. This stoking of a feeling of danger to the very foundations of the nation (and thus the People) is a powerful motivator by which to get your way politically; as such, it has been used by governments repeatedly over the past two centuries to achieve their goals – often for the worse.

There is a laundry list of examples of this particular form of rhetoric being used in practice for controversial, and even downright nefarious ends, particularly with respect to domestic political foes. During the French Revolution, for instance, the topic of the “republic in danger” was a constant theme of Girondin and Jacobin messaging through the wars with external and internal enemies. The very real threat of the outside European monarchies which sought to overturn the Revolution (for good or ill) was deliberately conflated with those who opposed the overreach of the Revolution at home. This “treasonous” behavior was punished harshly, especially in one infamous period: the Reign of Terror. The Terror is the most well-known era of the Revolution, and has given it its permanent association with the guillotine, show trials, and political murder. Under Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobin radicals in the Committee for Public Safety, thousands of political enemies (and often former friends like Georges Danton) were executed under the guise of national security, despite the lack of evidence or real peril. This spiraling political violence in the name of the security of the State eventually caught up with its architects, as they fell to the blade in due course, but not before wreaking havoc on France.

Decades later, across the Rhine, German statesman Otto von Bismarck used similar tactics to achieve similar – albeit far less violent – ends. Bismarck was a transformational political figure in the history of Germany, but he did not want any more transformation than that which he was personally comfortable with. This led to an extreme antipathy for his enemies on the left, particularly the Socialists, who grew in popularity throughout his career. Some of these Socialists were genuinely dangerous, bad actors who sought to violently overthrow the political system, but the majority were social progressives who sought broader representation in government and industry for the working class. Of course, Bismarck sought to tar the reputation of the latter majority with the actions of the fringe minority; he achieved this goal by claiming that all Socialists were terrorists who posed an immense threat to the State itself. This messaging only appealed to Bismarck’s conservative power base at first, but serendipitous events allowed him to expand its reach and appeal. In June 1878, a few weeks after an anti-Socialist bill was soundly defeated in the Reichstag, a radical Socialist agitator attempted to assassinate the head of state, Kaiser Wilhelm I, wounding him severely. Bismarck immediately used this terrorist act to his advantage, capitalizing on public anger at the would-be assassin to associate all Socialists with the attempted regicide; this rhetoric of Socialist danger to the State gained Bismarck the passage of a hardcore anti-Socialist law and a larger parliamentary majority.

The 20th century was a boomtime for this sort of problematic rhetoric among totalitarians and their imitators, all the way back to the halcyon days of World War I. Woodrow Wilson, the American President, was a major proponent of using the language of dangers to the State (something Wilson often conflated with democracy itself, starting a long-term trend) to crack down on political opposition. During the US’s brief involvement in the action in Europe, Wilson massively suppressed civil liberties and freedoms, jailing anti-war activists for their speech, criminalizing dissent, and eradicating the then-common use of German as an American language. Supreme Court decisions, including the infamous Schenck case (fire in a crowded theater), were used to buttress this blatant political censorship. Prominent political opposition figures, notably the Socialist Eugene Debs, were imprisoned as dangerous to the very fabric of American democracy and our mission abroad, merely for expressing dissenting views. (Note: Debs was only released in the next presidential administration by none other than the oft-maligned Republican Warren G. Harding.)

The idea of using a phantom menace to the State – and thus the People, at least in the 20th century – to crack down on internal political opposition was roundly embraced by Lenin and the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution. As a relatively small minority faction which succeeded in executing a coup d’état against the Russian government, the Bolsheviks had many political enemies which they needed to eliminate or sideline if they were to retain power. Associating the Party with the State and therefore the People allowed Lenin and his comrades to effectively and consistently turn even minor dissent into an existential threat to the Revolution. One excellent example of this comes in February 1918, when the Bolsheviks passed emergency measures ostensibly meant to defend the country against a potential further German invasion if the onerous terms of peace were not agreed. These measures were passed under a decree entitled “The socialist fatherland in danger,” and allowed for the creation of forced labor battalions as well as extrajudicial executions for anyone deemed “enemy agents, speculators, burglars, hooligans, counterrevolutionary agitators, [or] German spies.”[1] These measures, although facially meant to target a German fifth column, were in reality a ploy to go after Bolshevik political foes. Forced labor became the reality of Soviet life, filling the Gulag system with millions of slave laborers, while extrajudicial executions and empowered secret police (then the Cheka, later the NKVD) were turned against the Russian population writ large. In the words of historian Richard Pipes, “The two clauses marked the opening phase of Communist terror.” And all under the guise of protecting the State.

The Soviets would continue the use of such tactics under Stalin as well. Throughout the purges of the 1920s and 30s, Stalin labeled his own personal enemies as counterrevolutionaries or enemies of the State, thus making them easy fodder for the killing and imprisonment machinery of the Soviet apparatus. Camouflaging this naked political factionalism under the auspices of “State Security” gave cover to the regime both internally and abroad. Media lackeys and fellow-travelers like Walter Duranty of the New York Times ignored these rank atrocities in favor of an ideological narrative which presented the Soviet Union as a worker’s paradise that the US should imitate instead of as a charnel house which feasted on its own citizens in the name of progress. Likewise, the Nazi regime in Germany used the specter of danger to the State to eliminate political dissent altogether. After the Reichstag fire, which some historians consider a false flag operation, Hitler used his oratorical skill to blame Communists and other dissidents for the act, leading to widespread arrests and imprisonment in concentration camps like Dachau. But just like the Stalinists, the Nazis did not see political opposition as limited to those who sought to oppose the regime politically; they expanded this category of enemies to encompass any person deemed undesirable, from Roma, homosexuals, and the mentally impaired, to their main target, the Jews. Nazi propaganda was replete with the idea that a vast Jewish conspiracy was constantly attacking the German nation and seeking to enslave its people, an idea which was hammered home at every opportunity. As the Nazi State and territory expanded via conquest to the east – a land with the largest Jewish population in Europe – the rhetoric turned into utter destruction. The Holocaust itself was justified (and is still, despicably, by Holocaust deniers and antisemites of all sorts) by this language of an internal danger to the political system and regime.

Obviously, not all uses of this inflammatory rhetorical tactic are inevitably going to lead to such disasters as the Reign of Terror, the Gulag, or the Holocaust. Still, one should be wary when the message of an internal “danger to democracy” becomes more prevalent in political posturing. Unfortunately, we’re right in the middle of a surge in the use and abuse of this “threat to the State” narrative by the party in power, led by the President himself. Although the actual words used are far less directly totalitarian than those uttered by the leaders mentioned above, the message itself is no less pernicious. It is especially cynical in its linking of political threats to the Democratic Party with threats to the State and, through the State, to democracy itself. The talk of “democracy in danger” was strong when Trump was president – in many ways, more understandably so given that the supposed threat was in the White House. But it has persisted since President Biden’s inauguration in January 2021, and has accelerated significantly in the past few months as the 2022 midterm elections approach.

The communications strategy of Biden and the Democrats has focused heavily on labeling their political rivals as “a threat to the very soul of this country,” while simultaneously undermining key governmental institutions and financially supporting the most “ultra MAGA” Republican primary candidates for state and federal offices. By leaning into an issue with supposedly existential stakes, they hope to distract from rampant inflation, looming supply chain crises, flawed immigration policy, and foreign blunders. Democratic politicians have leveled fiery attacks at the Supreme Court, ones which exploded in rancor after the Court overturned Roe v. Wade this June. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) called the Supreme Court “illegitimate,” a charge that was topped by her junior partner Ed Markey (D-MA), who advocated its expansion to counter “stolen seats on a now illegitimate court, which are stealing the rights of American people.” Similar assaults have been launched at the Senate itself, as progressive members of a Democratic House seethe at the fact that their messaging bills and spending sprees are often stymied by the upper house’s procedural rules. The 60-vote threshold for the filibuster has forced legislative compromise – or nothing at all – on a party apparatus and activist class that have anathematized it as a concept. These supposed failures in the legislative and judicial branches have driven an even more antagonistic rhetorical turn in media and politics as the campaign season begins in earnest. Using the tried-and-true “democracy in danger” – in reality, more like “Democrats in danger” – tactic, the Democratic left is doubling down on labeling their political opposition as a threat to the country itself.

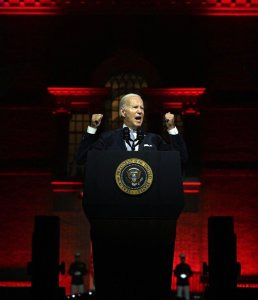

President Joe Biden has taken the lead on this crusade, but he is – to put it historically – no Godfrey of Bouillon. In one of his initial outings this campaign season, Biden called his presidential predecessor and the politics he represents “semi-fascism.” Asked to clarify, he said (either cryptically or confusedly): “You know what I mean.” This presidential use of the universally-reviled term ‘fascism’ is a major escalation in the rhetorical war; if the Democrats were fighting with mortars before, they’ve just advanced to full-blown field artillery. The administration wholeheartedly embraced this message in a major primetime speech given by the President on September 1 in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Many critics were accused of focusing on the aesthetics of the speech; reasonably so given that Biden spoke in front of a monument to democracy which was bathed in an ominous red light reminiscent of a Leni Riefenstahl production. He also stood with armed and uniformed Marines behind him, which both violated campaign law (this was absolutely a campaign speech) and added a tacit martial aspect to the speech. But – somehow – the content of the speech was more alarming than the production design.

In the address, the President claimed that “equality and democracy are under assault” by “an extremism that threatens the very foundations of our republic,” namely former President Trump and so-called “MAGA Republicans.” He also spoke of the threat they pose “to the very soul of this country,” a canned line that Biden uses in many of his speeches, and which in some ways is a progressive reinterpretation of the “blood and soil” discourse which was so familiar to 20th century historians. But the rhetorical assaults only picked up from there, with the President labeling his political rivals as “a clear and present danger to our democracy.” This expression is extremely inflammatory and directly advocates an antagonistic, whole-of-society approach to “defending our democracy.” Despite his later calls for non-violence, the overarching message of the speech itself, as well as the presentation and demeanor in which it was given, was to stop this imminent danger by whatever means necessary. If your political rivals are fascists who “do not believe in the rule of law,” “do not respect the Constitution,” “do not recognize the will of the people,” and are trying to “nullify the votes of 81 million people,” how would mere political action stop such a massive threat to the nation itself?

Although Biden claimed early in the speech that “not every Republican, not even the majority of Republicans, are MAGA Republicans,” he went on to associate any Republican who opposes abortion or supports recent Supreme Court rulings as part of those “MAGA forces” who are “determined to take this country backwards.” Clearly, that vastly expands the definition of “MAGA forces” to include all elected Republicans and a large portion of the country at-large. This huge swathe of people who happen to disagree with Democratic policy was unambiguously labeled by the President as “a threat to this country”; this mirrors the historic rhetoric discussed above almost perfectly. All in all, the speech itself was a true inflection point – not in the way Biden meant it, as the beginning of the end of the “MAGA Republicans,” but instead as a temporary high-water mark in the increasingly provocative rhetoric of “democracy in danger.”

The Biden administration attempted to soften the speech’s impact at first given the blowback from independents and Republicans, but has since chosen instead to amplify the “democracy in danger” trope in preparation for the coming elections. The President’s message has been widely praised by activists, sympathetic media, and politicians, amplifying its reach and prominence. In the days and weeks after the address, “democracy” has been on the lips of seemingly every partisan Democrat and pundit, including Hillary Clinton. Biden himself has repeatedly promoted this divisive and inaccurate messaging, in speeches, on Twitter, and through his mouthpiece at the Press Office. We will be seeing more and more of it as November approaches, likely with the tone of existential danger ramped up even higher. This is not good for the health of our republic, and portends a fall into a far more hostile, martial politics, one which often leads to physical violence.

Ironically enough, the abuse of “democracy in danger” rhetoric is a leading cause of actual democratic backsliding, as it stokes irreconcilable division based on faulty historical understandings and cynical political manipulations. At some point, angry people will feed the boy who cried wolf to the wolves themselves. And that’s not a path any lover of democracy or America should want to go down. Biden and the Democrats should beware of their own “democracy in danger” language. After all, slippery slopes are indeed slippery.

[1] Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution, 587-588.