“Surtout une Guerre de Chemin de Fer”: The Paramount Role of Railways in The Great War

Introduction

“Cette guerre est surtout une guerre de chemin de fer.” – French General Joseph Joffre[1]

World War I has often been historically associated with advances in military technology and the brutal impact those improvements had on the conduct and outcome of that war – and all future conflicts. Some of these technologies were invented to solve the problems that the Great War posed, while others were adapted and brought into use in ways that had not previously been possible or viable. Innovations in tactics and strategy were part and parcel of these novel technological approaches and came to define the war experience for many who lived through it, as well as in the popular imagination ever since.

Most people, when asked what image defines the First World War for them, would describe the impressive and widespread use of trenches and their development into semi-permanent military infrastructure; the use of and innovation in trench warfare – from electric lights and steel reinforcements to communication lines and well-organized trench networks – could certainly be considered a technological aspect of the war. Those trenches were intimately associated with another major technology of the war: the machine gun. Rapid-fire weaponry had been used in previous conflicts, but it had never been adopted on such a mass scale or used so effectively against troops following classic mass bayonet charge tactics; the success of the machine gun reinforced the stagnation of trench warfare, making it nearly impossible to cross the open ground of ‘No Man’s Land’ safely.[2] Other respondents would mention artillery as being the prime military technology of the war, as it caused seventy percent of all casualties, accounted for a great deal of wartime production, and was a near-constant aural presence during the four years of combat.[3] Artillery was not only present during the land battles of the war, it also was the prime means of naval surface combat, with ever-larger guns being implemented on battleships and dreadnoughts throughout the four years of fighting, some of which were able to hit targets nearly twenty miles away.[4] Yet artillery was not the only technology making an impact at sea – Germany used submarine warfare in a way that no other power had previously attempted, pushing an unrestricted submarine war against commerce in which “the surface navy was relegated to a position of support.”[5] This new, modern way of waging war was seen as barbaric and unprincipled by the Entente powers[6], and made a major impression not only on the future conduct of warfare – German U-boats were even more deadly in World War II – but on the Great War itself: without unrestricted submarine warfare, it is far less likely that the United States would have entered the conflict.[7]

The Great War also saw some entirely new technologies being developed or adapted for warfare, perhaps the most influential of which in the long-run was the advent of aerial combat. At the start of the war, planes were primarily used on a small-scale basis, focusing on artillery spotting, reconnaissance, and some air-to-air dogfighting. As the war progressed and transformed into the mass phenomenon that it would be remembered as, the role of planes grew immensely and changed in nature: now planes were used not only in a support role, they entered into their more recognizable modern roles as bombers and fighter planes delivering fire on enemy targets.[8] By the end of the conflict, the British had established the world’s first air force and the airplane had been fully integrated into combat tactics and planning, setting the stage for the next century of warfighting.[9] The other defining technology of twentieth-century warfare that debuted during the First World War was the tank. The tank made its first appearance under the British flag at the Battle of the Somme in September 1916, but it was often a disappointment during the war; tanks regularly broke down, had a very slow top speed, and had to deal with limited range.[10] Still, the tank made some difference, especially at the end of the conflict when lighter designs helped the Entente powers break through the German lines and concentrate firepower on military targets. The development of the tank as the prime weapon of a war of movement was still on the horizon at the end of the war, and it was not until the Second World War when it truly came into its own as a combat vehicle. Another military technology commonly associated with World War I was poison gas, which saw its greatest prevalence during this conflict, having been banned shortly thereafter in 1925.[11] Poison gas – not to be confused with the nonlethal tear gas which is still used in combat – was first used by the Germans against the French and Canadians at Langemarck near Ypres in April 1915[12]; it was controversial at the time and was labeled unchivalrous, repugnant, and demonic by critics on both sides.[13] The technology of gas attacks – and defense against them – advanced during the war, as different types of chemicals and more successful gas masks were developed at a rapid clip. These technologies – trenches, machine guns, tanks, artillery, planes, submarines, and poison gas – are all deeply connected to World War I in the popular and academic minds, yet none of them can accurately be seen as the technology which defined the war. To truly be the defining technology of the war requires not only involvement in every aspect of it, from start to finish, but also necessitates that the technology itself was defined by the conflict; most of the aforementioned technologies kept advancing in their military application and became more important to warfighting over time. There is only one technology which fully fits this paradigm: the railroad.

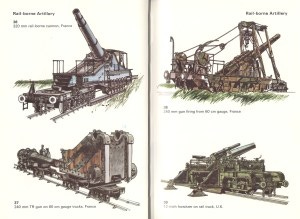

Railways were in many ways the technology which defined World War I; without them, none of the other technological marvels which we normally associate with the war would have functioned the way they did. Without railways, the trenches would be empty; there were very few – if any – soldiers who did not, at some point or another, travel via rail either to the Front or back home for leave. Without railways, artillery would be impotent; it was only through railways that the incredible number of shells fired on a daily basis were moved from the factory to the firing line. Shells were not the only materiel that were transported by rail – nearly all supplies which were needed to fight, feed, and function were shipped on rails. Railways touched the entire war, from the home front to the trenches themselves; one could travel almost the entire way from the safety of home to the very front lines on rails without walking more than a few hundred yards between junctions. Trains were not only used for the critical logistics which fueled the fighting, but also in direct combat. Armored troop trains, hit-and-run attack trains, and railborne artillery all served important purposes during the war, helping to provide combat support for foot soldiers and generating casualties on the opposing side. Trains were also used to great tactical effect to move troops rapidly between attack positions during battle, as well as evacuating whole divisions from the field. Railways were crucial in saving lives as well as taking them: ambulance trains in the hundreds brought injured servicemen from the battlefield to proper hospitals all throughout the war, likely reducing fatalities significantly.

The importance of railway technology and great power competition over those railways were a strategic factor in starting the war, the rails were used heavily during the fighting, and they even played significant symbolic and practical roles in the war’s end and the treaties which were signed to effect it. They were the prime focus of pre-war military planners, saw action in all theaters of war from Africa to the Middle East to Europe, and were used to great effect by each of the belligerents of the Entente and Central Powers. But railways were not only definitional in all aspects of the First World War, they were also defined by it. Never again were railways such a key component of warfighting as they were from 1914 to 1918. Largely due to the interwar development of the internal combustion engine and its ability to move goods and people in a cheaper, more reliable way to widely-dispersed locations without massive infrastructure investment, “the First World War would be the last European war in which the railways played a dominant role.”[14] This war saw the apex of military railway technology as a prime focus of logistics and combat, a role which they would never again play to such a high degree. The Great War saw the mass proliferation of rail throughout combat zones, but also helped drive the development of new railroad equipment, technologies, and management techniques and strategies to control civilian railway systems – all of which would shape the future of rail transit throughout the world.[15] All of these aspects of railways and their impact on the First World War have been evident since the war’s conclusion – and even earlier. As General Joseph Joffre, one of France’s supreme wartime commanders, said during the conflict: “Cette guerre est surtout une guerre de chemin de fer.”[16] Translated from the French, he said: “This war is above all a railway war.” General Joffre was right, both at the time and in the sharp light of history: The Great War was defined by railway technology, from beginning to end, from the home front to the trenches, strategically, tactically, and symbolically.

Railways Before the War

The development of European and colonial railways by the eventual belligerents in the pre-war era of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries laid the groundwork for the critical role that railways would play in the First World War.

Strategic Railways in Europe

Each belligerent power, on both sides, built and organized railways on the home front for dual use: civilian and military. With respect to military development, the powers all developed their railways in two main ways: their permanent lines were organized so as to be able to act as supply routes in the case of war and each power also developed their own version of light, narrow-gauge[17] field railways for wartime use.[18] The pre-war organization of railways and railway corps mattered a great deal in the mobilization and early weeks of the conflict. The table below presents a snapshot of railway organization in September 1914 and gives a glimpse into the various levels of development in each belligerent nation through the proxies of miles of track, number of locomotives, carriages, and wagons, as well as ratios of locomotives and carriages to route miles.

Table I: Statistics on Railway Infrastructure, September 1914[19]

LocomotivesCarriagesWagons Route MilesNumberPer 100 Route MilesNumberPer 100 Route MilesNumberUnited Kingdom23,71822,9989772,888308780,520*Belgium5,3704,3008010,00018690,000Germany38,95028,0007260,000154600,000France31,20014,5004733,500107364,000Russia45,35017,2003820,00044370,000Austria-Hungary28,40010,0003521,00074245,000

*Excluding over 600,000 privately-owned wagons.

To get a closer picture, it is instructive to look at each power on its own to compare and contrast organizational strategies; moving from west to east highlights some of the variations and similarities in development more starkly.

Britain

Of the European powers that would play a major role in the war, the United Kingdom’s home front railways would play the smallest role in actual combat – not too surprisingly for an island nation separated from the Continent, and the fighting which took place on it, by the English Channel. As the British had this maritime buffer, the organization of their railways was far less military-oriented, as “there was no question of building lines of invasion or lines to facilitate the massing of troops on a neighbour’s frontiers.”[20] Instead, the issues faced by the British railways before the war revolved around state involvement in private business – railway companies were privately-owned in Britain at this time – the measures which could be taken by the government in connection with these operators to make mobilization and supply as efficient as possible during wartime, and how railway engineering corps could be created and drilled for military use.[21] The private nature of British railway development and its focus purely on peacetime use, although an outlier with respect to peer nations in Europe, did have benefits for the war effort; “competitive building, encouraged by Parliament, had produced a plethora of alternative routes, wasteful in normal times and intolerable today, but invaluable in World War I conditions.”[22] These overlapping routes, which would serve military purposes given their redundancy[23], were operated by private companies which normally would compete against one another and could create inefficiencies in time of war. The British solved this problem by creating the Railway Executive Committee (REC) in November 1912[24], a group which consisted of management representatives from the nation’s largest railway operators and which would “control and manage the railways as a whole in the event of an emergency,”[25] namely war. This organization smoothed the transfer of responsibility for the railways during war from the myriad private operators to a state-controlled committee, but also ensured that those operators who were in the best position to know their own railways were involved in wartime operations.[26] With respect to the men who would operate, construct, and repair military railways during wartime, the British were fairly behind their Continental neighbors; they only organized formal military railway companies after their experiences in the colonial wars of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.[27] They did organize well once they decided to create these official companies, building “a permanent base and standard gauge training railway” to drill these railway troops during peacetime and prepare those who would be sent abroad in case of war.[28] Despite training only a relatively small number of railway troops before the outbreak of war in 1914, the British had an advantage due to their large-scale adoption of civilian rail and the slew of railwaymen who had gained important skills through their civilian careers and could be relied upon in case of conflict.[29] Altogether, according to J.A.B. Hamilton, “the railways of Britain went into the war with a sensible and workable organization.”[30]

France

Britain’s neighbor across the Channel and fellow Entente power France had a completely different railway organization before summer 1914, largely due to its catastrophic experience in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War where the nation was defeated soundly by the various German states which then unified into a major power on France’s doorstep. This war experience was foundational to France’s approach to military organization henceforth, and railways were no exception. Before the Franco-Prussian War, France’s railways were “developed on principles which practically ignored strategical considerations, were based mainly on economic, political, and local interests, and…failed to provide adequately…for the legitimate purposes of national defence.”[31] They would not make the same mistake leading up to the next war, which all French certainly anticipated would come. Preparing for this eventuality necessitated a complete reorientation and expansion of the French railway system. According to railway historians Augustus Veenendaal and H. Roger Grant, “the new French system was largely set up as a defensive one, contrary to the German system that was chiefly meant to facilitate an offensive against France.”[32] These defensive strategic railways were a vast improvement on the earlier system and were paramount in France’s preparations for and actions during the war. There were several new developments, all of which were defense-focused and meant to ease troop movements and supply logistics for the military. First, the confusing jumble of railways in and around Paris was simplified and reorganized so as to ease congestion around the capital, ensure that trains destined for areas outside of Paris would not have to pass through it to reach their destinations, and connect Paris with other important strategic areas.[33] This was accomplished by means of a system of circular ‘ring’ railways which surrounded Paris with concentric circles and extended out to link cities as far as Rouen, Amiens, Reims, Troyes, Epernay, Soissons, and others; these ring railways were connected by trunk lines to other crucial military centers like Orléans and Tours so as to ease troop movements.[34] New railways were built to link important harbors, strategic interior points, fortresses, military bases, and arsenals to each other and to the lines which radiated out towards France’s frontiers.[35] Some of the lines linking various frontier posts like Verdun and Belfort were narrow-gauge rails which would facilitate and expedite munitions transfers both within and between the fortresses during wartime; this development was largely led by the French artillery corps, which saw the need for rapid movement of munitions between frontier fortresses in case of German invasion.[36] Not only did the French build new railway infrastructure to prepare for war, they also greatly expanded and renovated existing lines and stations, often doubling or quadrupling existing tracks for the purpose of speeding transport and creating positive redundancies, as well as building special long platforms at arsenals to “allow the rapid entraining of men or material in case of need.”[37] The French also adopted the idea – originating in Germany – of railway troops, and had a strong system of training and a large number of men dedicated to this task before the war broke out.[38] France created Field Railway Sections and railway troop battalions, which were “permanent military corps charged, in time of war… with the construction, renovation and operation” of military railways[39]; these troops were both volunteers and conscripts who were suited for railway work by their prior occupation as railway workers or operators.[40] They were trained in technical academies run by the military and were drilled through regular work on certain French railways during peacetime so as to practice repairs and construction under real-world conditions.[41] Similarly to the British approach, French officials ensured that all railways would come under the auspices of the state in the event of war; they differed in that they segmented French territory into the Zone of the Interior – where military transports were given priority on civilian rails run by the War Minister – and the Zone of the Armies – where all railways were managed and run by the Commander-in-Chief of the Army.[42] This dichotomy was necessary in France and not Britain due to the fact that combat on French soil was expected, whereas Britain was not anticipating any fighting on the home front. Overall, the French were well-prepared for war due to their embrace of a strategy of national defense which revolved around strategic railways and military organization.

Germany

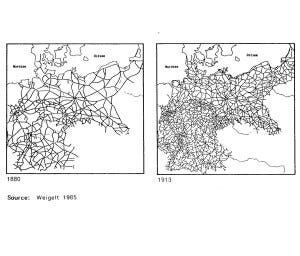

Germany was without a doubt the leading rail power of the pre-war era and was a pioneer in the development of strategic railways for use in mobilization and wartime, as well as a major innovator in railway technology. Railways, although developed first in England, were wholeheartedly embraced by the German states in the mid-nineteenth century and proliferated rapidly across the country. The Germans propagated railways quickly and invented new technologies that improved railway travel and logistics; one such innovation was the weldless steel railway tire, invented by the German industrialist Alfred Krupp, which strengthened train wheels so that they would not break so easily under the stress of friction and the weight of cargo.[43] This embrace of railways was reflected in the number of lines and their overall spread across the whole of the German Empire. Figure I above shows a comparison between the German railway system of 1880 and the network available just before the start of the war in 1914; notice the massive increase in branch lines, city-to-city connections, hub-and-spoke infrastructure, and rail lines near and along the German borders. In the thirty-three years between the two images, German rail infrastructure rapidly advanced and was developed for specific military purposes. The Germans were able to more easily push the growth of strategical railways than their French counterparts as they had nationalized – or, more accurately, federalized – their railways in the period after unification, with each federal state running the railways within its own territory.[44] According to the German scholars G. Wolfgang Heinze and Heinrich H. Kill, “At the turn of the 20th century, 59,082 km of the 63,794 km of German railways belonged to 8 state railways. These states were Prussia, Hesse, Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and the small but opinionated duchies of Oldenburg and Mecklenburg-Schwerin.”[45] These strategic railways, which were dual-purpose military and civilian rails that would transfer to purely military use during wartime, were organized “for every possible theater of war.”[46] Strategic lines were built even in the absence of civilian demand, junctions were made so as to facilitate through traffic to ease mobilization and logistics, and operations were standardized to make moving to a full war footing faster.[47] In the west, the Germans built several lines to and along the borders with Belgium and Holland, so as to avoid the heavily-militarized border with France in case of conflict. In the case of Belgium, the Germans developed “a complete network of strategical lines radiating from Aix-la-Chapelle, the Rhine, and the Moselle to the new Malmedy-Stavelot line (crossing the frontier of Germany and Belgium), the said network affording the means by which troops from all parts of the German Empire could be poured in an endless succession of trains on to Belgian territory.”[48] With respect to Holland, the German approach was similar: building of railways which hugged and sometimes crossed the border so as to facilitate potential invasions during war.[49] In the east, “there was built by Germany another network of strategical railways which connected various military centres with lines running parallel to the frontier, and having branches to points within a few miles thereof, so that troops could be concentrated wherever they were wanted.”[50] The Germans also built several lines along the sparsely-populated coasts of Pomerania and East Prussia and then south along the border with Russia; these railways were meant to move troops “not only by different routes to many points along the Baltic coast or the Russian frontier, but, also, from one of these coastal or frontier points direct to another, as may be desired.”[51] These railways – particularly those in the east – were so expertly designed that, according to historian Henry Jacolin, “after the war broke out the trains could circulate every 20 minutes, enabling the rapid transport of troops.”[52] The Germans took other military aspects of railways seriously too. As stated earlier, the Germans were the first European nation to create railway troop battalions meant expressly for use on the rails during wartime. These troops were highly trained and had combat experience from the successful Franco-Prussian War, as well as being used in Germany’s colonies to develop military railways.[53] Germany created a major military training ground outside of Berlin solely for the use of the railway divisions; “The railway troops could exercise here to their heart’s content, laying and destroying tracks, building bridges and blowing them up again, handling steam locomotives and rolling stock, and loading and unloading ordnance and other equipment such as heavy mobile kitchen cars to feed the troops in the field, in short, everything expected from them in times of war.”[54] The troops were not the only non-infrastructure preparation that the Germans made for rail war: they even designed their locomotives and rolling stock[55] for operation in other countries with different rail systems, including designing locomotive steam funnels in multiple parts in case bridge crossings were lower than those in Germany.[56] According to Denis Bishop and Keith Davis, of all the belligerent powers, “Germany was without doubt the most thoroughly prepared and experienced. She had a large and expert military railways department; the civilian railway personnel, especially the Prussians, were organized largely on military lines and their equipment and railways were easily convertible to military use.”[57]

Austria-Hungary

Germany’s Central Power ally Austria-Hungary was far less prepared than her Germanic sister for a railway war, though not for lack of trying. The Dual Monarchy adopted railways before the Germans and, according to historian Pieter M. Judson, “The state recognized the vital importance of railroads both for economic and military purposes,” even as early as the 1850s.[58] One of the challenges faced by the Austro-Hungarians was the public ownership of railways, which was a feature of the Habsburg system from the start; privatization of these railways and of future railway concessions was the spark which set off a railway construction boom in the nation.[59] Railway projects included a controversial line through the Sandžak region of modern-day Serbia and Montenegro which angered the Russians and contributed to the climate of danger in the Balkans before the Great War.[60] After the annexation of Bosnia by the Dual Monarchy in 1908, there was a narrow-gauge railway built, as well as talk of further links to Turkey via rail; other Balkan railway projects were incomplete before the outbreak of war, including the linking of Dalmatia to Zagreb and Budapest via Bosnia.[61] At the same time as these theorized railway lines in the Balkans were failing to materialize, internal railway links in Hungary were expanding rapidly: the Hungarian railway network grew nearly tenfold from 1867 and 1907.[62] Still, unlike Germany, Austria-Hungary “had many gaps in its railway system, and there was no railway line following the border. Such infrastructural issues like a weak connection between Galicia and Hungary and a lack of any connection between Transylvania, Galicia and Bukovina had a negative influence on warfare.”[63] According to Veenendaal and Grant, “The Austro-Hungarian army staff was for many years chiefly concerned about the threat from the East and pressed for the extension of the railway system in Galicia and southern Poland. Only three railway lines reached Lemberg – present-day Lviv, Ukraine – the center of Austrian power. And of these three, only one was partly double tracked, the rest single track.”[64] Even with these railway issues near what would become the front lines of the conflict, the Austro-Hungarians had experience using military railways in Bosnia, stockpiled materials and equipment that could run on this line and others like it[65], and created groups of railway troops on the German model, albeit on a much smaller scale.[66]

Russia

Of all the European powers, Tsarist Russia was by far the least advanced in railway technology and infrastructure; this is hardly surprising given the regime’s reputation within Europe for its ‘backwardness’, as well as Russia’s late – but swift – industrialization process. Russia’s railways were at an embryonic stage when the war broke out and they had far less track than her adversaries or allies possessed; “whereas for each 100 square kilometers, Germany had 10.6 kilometers of railways, France 8.8, and Austria-Hungary 6.4, Russia had a mere 1.1.”[67] Russian strategic railways were largely either nonexistent or developed solely with defensive purposes in mind; according to the historian Reinhard Nachtigal, railway construction in the late Russian Empire was “characterized by predominance of economic demands in railway planning and did not foresee the strategic use of many railway lines in case of war.”[68] Commercial use of railways was a far more important objective for the Empire than was spatial control via railways, an approach that put them behind the other powers, particularly Germany, who took a different tack.[69] Russia also ran into problems due to its odd gauge size: the rails were five feet apart, a gauge that was not used anywhere else in Europe.[70] This large gauge was used internally in Russia, but was not linked with the standard gauge lines built in Russian Poland, which followed more conventional European sizing.[71] Furthermore, most Russian lines were single-tracked, including major strategic lines linking ports with military bases and cities; the vaunted Trans-Siberian Railroad linking European Russia with the Pacific port of Vladivostok was single-tracked, as was the sole narrow-gauge line running from Archangelsk to the center of the country – the port of Murmansk had no railway connection in 1914.[72] Still, the Russians were not entirely unprepared for the railway war which started in 1914, especially when it came to narrow-gauge military field railways. For starters, they stockpiled “hundreds of miles of portable track sections [that] were ready for use behind the front, together with about 240 steam locomotives and more than 1,100 wagons, plus some 1,200 smaller and lighter wagons for horse traction.”[73] To construct and operate these light railways, the Russians had their own railway battalions, nine of which existed in 1914; they were not inexperienced, winning “laurels with the construction of the Trans-Caspian and the Trans-Siberian railways” through difficult terrain and in harsh conditions.[74] Even with these mitigating factors, Tsarist Russia was far and away the least advanced belligerent in Europe regarding railways.

Railways in Other Theaters

The First World War did not earn its moniker by being fought solely in Europe, and railways played a major role in the Middle East and Africa as well. The pre-war development of colonial railways by the European powers, as well as the organization and expansion of railways in the Ottoman Empire before 1914 are important to understanding the impact of railways in these regions during the war.

The Ottoman Empire

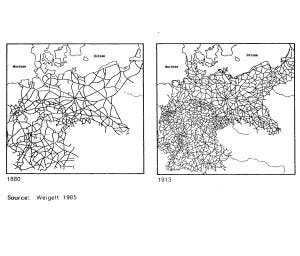

The Ottoman Empire, although not initially involved in the war, had some important strategic railway infrastructure that would play a part later in the conflict. Railways in the Ottoman Empire were also a key factor in rising tensions between the British and Germans, the world’s two dominant powers before the outbreak of the Great War; as the Ottomans were fading into irrelevance and losing territory in Europe, various European powers wished to take advantage for their own commercial and strategic purposes.[75] Britain had long-term interests in the Middle East, many of which revolved around protecting the approaches to Britain’s imperial crown jewel: India.[76] Germany wanted to strike at these interests in the pursuit of her policy of Weltpolitik, or world politics[77]; her main means of doing so was through construction of “the single largest German railway investment overseas,” the proposed Berlin to Baghdad railway.[78] The proposed route of this extensive railway can be seen in Figure II above. This railway, the construction of which was granted in a ninety-nine year concession to Deutsche Bank in 1903, was meant to link the heartland of Germany with the Middle East, particularly with the oil fields of Mesopotamia – Deutsche Bank also received a forty-year concession for Mesopotamian oil exploration.[79] According to Veenendaal and Grant, “alarm bells started to ring in London as it was – correctly – surmised that the Germans had in mind to extend the railway from Konya [in Anatolia] all the way into Mesopotamia with Baghdad or even the Persian Gulf as the ultimate goal.”[80] German presence in the Middle East was both novel and threatening; it was seen by contemporary British commentators as the start of a German push to deprive Britain of her Egyptian territory, her place in the Persian Gulf, and “threaten the gates of India and the ocean highway to Australia.”[81] This was perceived by the British – and the Russians, who had long-term interests in Persia and designs on Ottoman territory – as a shot across the bow, one meant to attack commerce and provide a strategic menace to important territory.[82] Given the serious past friction between the British and Russians, it was challenging to bring them together under the banner of mutual interests, but the Berlin-Baghdad Railway certainly did this; it has been argued that the development of this railway and the German involvement in Constantinople more broadly helped bring about the Anglo-Russian entente that played such a large role in the First World War.[83] Not only did the railway foster the Anglo-Russian entente, it became “a major conflict of national interests” that “helped unite the Entente powers against Germany… [leading] Germany into a fear of encirclement, her increasing involvement in the Balkans, and her dangerous alliance with Austria.”[84] Despite its important role in the buildup to the conflict, the Berlin-Baghdad Railway project was not completed by either empire before they fell in the aftermath of the war. According to Veenendaal and Grant, “At the outbreak of the First World War the railway had arrived at a place 200 kilometers west of Nisibin, modern-day Nusaybin in the north of Iraq. Meanwhile construction had begun north from Baghdad through the level country along the Tigris River as well, and Samara, 120 kilometers north of Baghdad, had been reached by 1914.”[85] The railway would be used during the war, but we will touch on that later.

The other major strategic railway of the Ottoman Empire was related to the Berlin-Baghdad Railway in that it was meant to link up with it and provide the Turks a clear route along the Red Sea and near to Egypt and the Suez Canal[86]; this was the Hejaz Railway located largely in modern Saudi Arabia. This line ran from Damascus in Syria – a major Ottoman stronghold – to the Muslim holy sites of Mecca and Medina, speeding up travel for Hajj pilgrims and allowing them to enter by way of Ottoman ports, avoiding the British-run route through Egypt.[87] As with the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, construction of the Hejaz Railway was done “with German thoroughness, with solid masonry stations and bridges, German rolling stock, and German telegraph instruments.”[88] According to Sean McMeekin, “the Hejaz line embodied the German-Ottoman partnership even better than did the Berlin-Baghdad project. The Kaiser, after all, had declared himself the ‘friend for all time’ of the sultan-caliph and his Muslim subjects, which gave political point to the Hejaz railway.”[89] Although the religious message was promoted upfront by the Germans and Ottomans, in reality the Hejaz line was just as much a strategic military railway as it was an expedient for the Hajj.[90] The railway ran through the heartland of the Arab tribes, where the Ottoman central authorities had a smaller presence and often dealt with insurrectionary subjects. Thus, “the railway would be the ideal vehicle to bring Turkish troops to places of unrest and to secure the provisioning of the large Turkish garrison in Medina. And the line looked the part, with heavily fortified station buildings and water tanks, surrounded by barbed-wire barracks and machine guns, and manned by Turkish garrisons equipped with modern German firearms.”[91] Given the line’s visual trappings and the role it was to play in the Great War, it is certainly the case that this was a military railway, regardless of the Ottoman propaganda.

Africa

Colonial railways in Africa were built by all of the European imperialist powers who became belligerents in the First World War – the British, French, and Germans – both as a means of spatial and political control, as well as a commercial expedient meant to bring goods to market rapidly. The British had developed significant railway infrastructure in their colonies in southern Africa, much of which was tested militarily during the Boer War.[92] These railways were not initially meant for military use, instead focusing on commercial opportunities and connections between British colonial regions. Britain even had its own version of the Berlin-Baghdad dream, but located in Africa; the famed imperialist Cecil Rhodes advocated tirelessly for a railway that ran the length of Africa, from the British Cape Colony in the south to Egypt and the Suez in the north.[93][94] This dream never became a reality for Rhodes or the British, but it did manifest itself in the gauge size that the British used in Africa; this Cape gauge was used throughout British Africa and is still a lingering reminder of the railway which might have been.[95] The French built their own railways in their African colonies as well, particularly in their North African possessions. The railways initially built in Algeria and Tunisia were meant “chiefly for economic reasons but also for easy transportation of troops.”[96] The building of these lines continued into the war years, where narrow-gauge lines were built “from Biskra, the end of the standard gauge line from the coast, to Touggourt, a southern outpost not far from the Tunisian border. Oil had been found there, becoming a vital fuel during the war.”[97] Finally, the Germans could not be left out of this colonial railway boom, and as usual they were well-organized once they joined the game. The German politician and colonial advocate Karl Helfferich argued that “the single most important measure that had to be taken in the colonies to assure their economic development was the creation of an efficient transportation infrastructure.”[98] The government and private sponsors took him up on his challenge, but this was a relatively late development, only kicking off in earnest in the last decade of the nineteenth century.[99] According some Britons at the time, these German railways were meant – similarly to the Baghdad Railway – as a means to dominate Africa and absorb the colonies of other European powers.[100] These observers, who were certainly not neutral, saw Germany as attempting to create an African Empire through its use of railways to increase its influence and ability to take over rival colonies, especially the strategically important and resource rich Belgian Congo, French North Africa, British Rhodesia, and Portuguese Angola.[101] Although the German railways never achieved the domination that some worried Brits anticipated, they did serve strategic and military purposes. According to Veenendaal and Grant, “It was in German South West Africa, present-day Namibia, that railways were constructed for purely military reasons. In 1897, German troops began the construction of a line on the 600mm (1ft 11in) gauge, just like the Heeresfeldbahnen, the military railways at home.”[102] These lines were mirrored in the development of railways in German East Africa, where railroads were in construction to link the coast at Dar es Salaam with the interior at Lake Tanganyika; these were not fully completed on the outbreak of war, but did serve important roles in combat during the conflict.[103]

War Plans, Mobilization, and the Start of War

The pre-war development of railways, especially in Europe, deeply influenced the war planning of the powers, set the stage for the greatest military mobilization to that point in history, and – in the early days of the conflict – played a key role in determining the stakes and the battlefields which would be contested for the next four years.

Railroads and War Plans

Military strategists and thinkers in the early twentieth century were obsessed with the idea of detailed advance planning of campaigns, so as to catch one’s opponents off guard or beat them to the punch, forcing the fighting into a paradigm already chosen by the planner. According to the British historian A.J.P. Taylor, this was very much in line with the civilizational attitudes of the late nineteenth century and the turn of the twentieth; the civilization of this age “rested on the belief that certainty, and therefore security, could be indefinitely prolonged into the future. The most obvious example of this was the railway time-table. With its aid, a man could state, down to the minute, precisely where he would be a month or a year from now.”[104] This focus on future-oriented planning based on railway timetables was not merely a civilian fixation – it also heavily impacted the military planning that would reach its rigid zenith in the First World War. The planners worked in a military bubble, very rarely devising their strategies with the aid of the political and diplomatic figures who would be crucial in the leadup to a conflict and its early stages[105]; oftentimes these plans were not even shared with civilian politicians or leaders, some of whom, deferring to military leadership, “tactfully did not ask” to be brought into the fold.[106]

Each power had a different war plan, varying in flexibility and timing, but they all had plans for a future conflict. Given the tangled alliance system which has often been blamed for causing the Great War, it is interesting that there was little coordination among allies – both of the Entente and the Central Powers – relating to their war plans. Many of the plans did not mesh with those of their allies, no powers planned together for joint use of equipment or intelligence assets, and there were even issues of who would be in command of any joint operations.[107] Besides these significant issues of coordination and planning, the powers each had to rely heavily on their railway infrastructure to determine their ability to quickly mobilize; in the minds of the planners, “Whichever power completed its mobilization first would strike first and might even win the war before the other side was ready. Hence the time-tables became ever more ingenious and ever more complicated.”[108] Because of this assumption that the success of mobilization meant success in war, the strategic railways described earlier became central to the possibility of victory; better organization would lead to faster mobilization and greater territorial gains. One consideration which none of the powers brought into their plans was enemy interference; each power assumed that all belligerents would mobilize almost simultaneously and thus enemies would not be able to, through their own actions, stop the successful execution of pre-conceived war plans.[109] This was a fatal error that would blow a hole in the certainty of the planners and would influence the outcome of the war.

The process of mobilization itself was a detailed and intricate one which relied heavily on absolute perfection and minute-by-minute planning. Each power began things differently, but the general process went like this: signs were given in public places for recently discharged soldiers to meet in a designated place, from which they would progressively join larger and larger army groups as they moved closer to the theater of combat.[110] Men were not the only ones mobilized – artillery, materiel, munitions, and, crucially for the First World War, horses and their fodder, were also moved to the combat zones as rapidly as possible.[111] Mobilization had its own inexorable logic and inertia once it began, much of which originated from the reliance on railways:

Once started the mobilizations could not be stopped. Of course, all troop transports went by rail and all timetables for these mass movements had been made many years earlier and could not be changed on short notice. … Any attempt to tinker with [the timetables] would lead to serious delays, congestion, or even collisions. The deployment of an army by rail, once started, could not be altered. Statesmen and generals alike had become completely dependent on the railways.[112]

Before discussing the actual mobilization in summer 1914 and its outcomes for each power, it is instructive to understand a bit more about their different approaches to planning and how the railways played their role in that drama. For the British, mobilization was a multi-part process, as any British Expeditionary Force (BEF) would have to not only mobilize in Britain, but then also transit the English Channel to arrive at the most likely place of conflict in northern France.[113] The freedom of action which would have been provided by Britain’s island status was curtailed by military planners, as they essentially guaranteed the French that the BEF would assist the French on its left flank[114]; although they could indeed decide whether to go to war, the British were – once war was joined – locked into going “to Maubeuge in north-eastern France and nowhere else in the wide expanses of Europe.”[115] Before the war, the British did do a practice run of a small mobilization during scheduled Army maneuvers in 1913; this was separate from the secret plans to aid France, but it was a useful trial run of railway operations.[116] The French, unlike the other belligerent powers, had only one possible strategy: fighting a war against Germany, likely defensive, along the line of the Vosges Mountains on the border.[117] As detailed earlier, French railways were deliberately designed with this strategy in mind: they had rails meant almost exclusively for speedy mobilization to what military planners assumed would be a “great battle of the frontiers.”[118] As the war drew closer, French strategists began to worry about a potential German advance through neutral Belgium and shifted to a strategy of aggression that would see the troops still moved to the frontiers by rail, but attacking instead of defending.[119] Even with this change in posture, mobilization for the French did not mean war, as the soldiers moved to the frontiers would have to wait for instructions before attacking into German territory.[120]

The Germans, famously, had crafted a detailed and inflexible plan which they thought would guarantee them victory even in a two-front war: the Schlieffen Plan. This plan was for the Germans to mobilize quickly, taking advantage of the forecasted slow mobilization of the Russian enemy on the eastern front and pushing the vast majority of German troops to attack France.[121] While the bulk of the German troops overran France, the smaller group in the east would execute a holding action against the Russians, ideally losing only a small amount of territory before the victorious troops of the Western Front would entrain and reinforce them.[122] The German planners were extremely confident in the efficient operation of their military and strategic railways, so confident in fact that they allowed no room in the Schlieffen Plan for any sort of delay, error, or confusion in the mobilization process or the rail borne transport.[123] As the Schlieffen Plan was more deeply entrenched in the German military staff, it became more and more detailed and inflexible. For instance, troops would have to be pushed in an incredibly fast manner through a lone junction on the border at Aachen (Aix-la-Chappelle) before the French could react, a difficult feat of railway timetabling and engineering.[124] Because this required the constant movement of army groups, no single group could wait for a declaration of war before invading enemy territory; this made the German mobilization plan a guarantee of war.[125] The development of German railways did play a role in this planning, especially the strategic lines running near borders that proliferated in the pre-war era. Despite this strategic railway construction, German railroads in the east were still less dense and developed than was initially planned: “Although the government put up millions of Reichsmark for the purpose, development of the eastern network was never good enough in the eyes of the military, and plans for the mobilization against the Russian foe had to be adjusted because of this lack of an adequate number of lines.”[126] To further expedite troop mobilization and entrainment – a necessity if the Schlieffen Plan was to be followed properly – the Germans segmented their army groups, having them first meet at a home base (Etappenanfangsort) before traveling to assembly stations (Sammelstationen) closer to the front.[127] This multi-step process allowed the German armies to prepare and move troops and supplies as fast as was possible.

The other powers on the Eastern Front, Austria-Hungary and Russia, had mobilization plans that differed widely from those of the other belligerents and had little to do with the war that would be fought in 1914.[128] The Austrian strategy was fairly flexible compared to her ally Germany: mobilization was only a precursor to war and would not force the Austrians into any predetermined strategy or geographical position.[129] They could therefore orient their forces to face the Russians in Galicia – this was where the mass of their forces was pointed towards at the outset of war – or shift armies to face off against either Serbia in the Balkans or Italy along the Alpine border.[130] This all looked excellent on paper, but would be sorely tested in the early days of the conflict. The Russians, on the other hand, had a strategy that was simultaneously both flexible and rigid; the target of their mobilization was not predetermined, allowing military leaders to decide on the next actions, but they had plans that, once started, made adjusting very difficult.[131] For example, if the Russians chose a limited mobilization against Austria-Hungary, they could not later change to a general mobilization without massively complicating the timetabling system – some trains would be operating days or weeks ahead of others based on alterations in the plans.[132] The Russians did do a good job, however, of getting mobilization plans to the appropriate people and departments; “All railway lines or groups of lines were supplied with excerpts of these plans pertaining to their section, and the upper echelons of the staff knew where the plans were kept.”[133] All of the mobilization plans of the various belligerents would be sorely tested by reality in the summer of 1914.

Mobilization: Success or Failure?

The British Major-General Sir Edward Spears, who was present for the French mobilization in August 1914, left an incredible eyewitness account of the problems inherent in the process and describes the importance of railways and planning:

If the mobilization is delayed or slow, the enemy will be enabled to advance with a fully equipped army against an unprepared one, which would be disastrous. The time factor also makes it essential that the armies, once mobilized, should find themselves exactly where they can at once take up the role assigned to them. There is no opportunity for extensive maneuvers: mobilization is in itself a maneuver at the end of which the armies must be ready to strike according to the pre-arranged plan. The plan is therefore obviously of vital importance. … From the moment mobilization is ordered, every man must know where he has to join, and must get there in a given time. Each unit, once complete and fully equipped, must be ready to proceed on a given day at the appointed hour to a pre-arranged destination in a train awaiting it, which in its turn must move according to a carefully prepared railway scheme. … No change, no alteration is possible during mobilization. Improvisation when dealing with nearly three million men and the movements of 4,278 trains, as the French had to do, is out of the question.[134]

How did this supremely intricate, inflexible planning work out when it was put to the test in mid-1914? Each belligerent power had varying levels of success in this endeavor, some of which would influence the conduct of the rest of the war.

The British mobilization, although far smaller in scale than those of the Continental powers, was seen as a massive success. This was almost not the case, however, as the War Council argued for a landing in Belgium versus France so as to help the beleaguered neutrals; this was stopped by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Charles Douglas, who maintained that “everything had been arranged for landings in France and French rolling stock was set aside to transport the troops forward,” so a last-minute change would prove disastrous.[135] Thankfully for the British, Douglas’s advice was heeded, to excellent effect. Not only did the first wave of troops reach their approved destinations without delay, reinforcements continued flowing to British ports and across the Channel in an even more efficient manner as time went on.[136] To put this success into statistics, from the declaration of war on August 4 to the end of the month, the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) ran 711 extra trains on top of usual service carrying 131,000 men, 39,000 horses, & 344 heavy guns to Southampton to cross to Le Havre via ferry without any delays or breakdowns.[137] In one twenty-four hour period from August 21 to August 22, seventy-three trains ran to the crossing points, leaving every twelve minutes on a rigidly-adhered-to timetable.[138] In a feat unmatched by her Continental counterparts, Britain was able to achieve this mobilization without impacting civilian travel at all; her privately-built redundant lines proved valuable in this case.[139] The execution of this mobilization was so smooth that the Germans did not even realize that the BEF had landed on the Continent until they confronted one another at Mons[140]; this was a coup of the highest order for the British. Even the great commander and Secretary of State for War Herbert Kitchener agreed, saying that “The railway companies…have more than justified the complete confidence reposed in them by the War Office.”[141]

The French and Germans executed their mobilizations successfully and rapidly, but each ran into issues early in the war due to enemy interference and the inability of planners to take into account uncertainty; these issues will be touched on in the following section. The French success in mobilization via rail was celebrated by the French government and echoed by the publication ‘Journal des Transports’, which declared that “One can justly say that the first victory in this great conflict has been won by the railwaymen.”[142] From the start of full mobilization on August 5 to its completion on August 19, the French ran nearly 4,500 military trains, not including the several hundred which ran supplies to the frontier fortresses.[143] The one ‘what-if’ of the German mobilization involved a misinterpreted missive from the British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey, which led the Kaiser to believe that the British guaranteed French neutrality in the event of war focused in the east; the Kaiser wished to stop mobilization against France, which his general Moltke the Younger claimed was impossible as it would require the “rerouting of 11,000 trains.”[144] This put a stop to the Kaiser’s plan, and the war came shortly thereafter.

The mobilization of the eastern powers, Russia and Austria-Hungary, was not nearly as well-executed as was that of the British, Germans, or French. The Austrians had significant issues even though their plans were, on paper, the most flexible of any power. According to Taylor, “When the time came, the Austrians put off mobilizing as long as they could and then improvised in an atmosphere of chaos.”[145] Austria-Hungary began mobilizing mainly against their foes in Serbia, but had to quickly shift gears when war was declared on Russia as well; the Russian and Serbian fronts were on opposite sides of the country and mobilization in one was reducing warfighting capacity in the other.[146] As the Balkan mobilization came first, the Dual Monarchy was faced with a significant troop deficit on the northern front against Russia; the mobilization and timetabling could not be altered without severe consequences for both fronts, so the Austro-Hungarians had to gamble on a quick victory in the south followed by entrainment to the northern frontier.[147] Russian mobilization was also a mixed-bag, with some successes and other failures. To start with, the Russians had a challenge which the other belligerents did not: the vast size of its territory. This scale, combined with the dearth of strategic railways mentioned above, made Russia’s mobilization slower than their counterparts; for comparison purposes, a soldier in the western nations generally only “had to travel 200-300 kilometers from his home to the induction point; in Russia this distance was 900-1,000 kilometers.”[148] The Russian mobilization, as slow as it was, was still faster than her enemies Germany and Austria-Hungary anticipated: they had assumed that Russia would take about thirty days to mobilize, but a full two-thirds of the Tsarist army was mobilized on day eighteen.[149] This allowed the Tsar to stylize mobilization as a great success, as “there were no major failings and railways transported more troops than planned,” which the Tsar claimed was “magnificent”.[150] Underlying this claim of success was a more complicated story. The overall mobilization process lasted much longer than planned due to the movement of troops from deep in Siberia to the front lines, a process which was not concluded until early 1915, and one which was complicated by infrastructure failures and single-track lines.[151] Also, unlike their British ally, the Russian railways were unable to restore the civilian and commercial timetables after military mobilization, something which made logistics during the war less efficient.[152]

The Early Rail War

In the first weeks and months of the war, railways proved immensely important. Three regions in particular are worth exploring in more detail with respect to the early days of the Great War: the front in Belgium and northern France, the eastern front of German and Russian conflict, and the Galician front where the Austrians and Russians clashed.

Belgium and Northern France

Belgium was the first nation impacted by the First World War, as the Germans invaded it as part of the Schlieffen Plan. The Germans planned, using their strategic railways to the Belgian border, to rapidly move troops through the neutral country and “make a sudden descent on France by rail, and then to rush the main body of her troops, also by rail, back through Germany for the attack on Russia.”[153] This plan was derailed by “strong Belgian resistance, including extensive demolition of railway infrastructure, delay[ing] the advance and the use of the network to supply German forces.”[154] According to Veenendaal and Grant, “The retreating Belgian army had blown up the strategic bridges across the Meuse River near Namur, which slowed down the German advance considerably. Only in early September 1918 a single track could be used again.”[155] The Germans were prepared to repair this sort of damage – they had special trains called Bauzüge, which were full of ready-to-use construction materials meant to repair damaged lines – but the extent of the destruction was quite severe.[156] This deliberate sabotage by the Belgians made it very difficult for the Germans to coopt the Belgian railway network as they had planned. Many of the Belgian railway workers fled south and left the Germans to bring in their own operators to run the rail network, making seamless operation impossible[157]; “Even a month after the occupation of Belgium, barely 15 per cent of the railway network was operating despite 26,000 workers being drafted in.”[158]

The German push into Belgium caused ripple effects in the railway system of the French as well, especially early in the war. Refugees from Belgium and northern France flowed out of the warzone in mass numbers, most via rail:

…thousands of refugees from Belgium and the north and east of France, fleeing from the advancing armies, took the train to reach safety. More than half a million civilian travelers went through Paris between 25 July and 1 August, straining the facilities to the breaking point. …the greatest problem for the Dutch authorities was the enormous number of Belgian refugees fleeing from the violence. Especially during the fighting around Antwerp in September and early October, more than a million Belgians crossed the Dutch border to safety. Most came by train…[159]

These refugees pushed the railways to their breaking point, but they were not the only issues in this theater in the early part of the war. The Germans, due to their rapid advance through Belgian and French territory, quickly outran their supply lines, at one point they were over eighty miles from the nearest railhead, a distance which could not easily be covered by the horse-drawn transport which was needed to bridge the gap.[160] This changed over time as the front solidified and the armies dug in, but the French were likely saved from an early defeat by the inability of the German armies to utilize the full scope of the Belgian railway system. According to Pratt, “the action taken by Belgium was of exceptional value to the Allies, since it meant that, although Germany crossed the frontiers of Belgium and Luxemburg on August 3rd, it was not until the 24th that she was in a position to attack the French Army, which by that time had not only completed both its mobilization and its concentration, but had been joined by the first arrivals of the British Expeditionary Force.”[161]

Germany and Russia in the East

The role of railways was critical in the conflict between the Germans and Russians in the regions of East Prussia and Poland in the early part of the war. The Russians and Germans fought back and forth in this area in 1914, culminating with the rout of the Russians at the Battle of Tannenberg, which was heavily influenced by railway operations – this will be detailed below. After the Russian defeat and subsequent retreat, they “had taken much of the rolling stock and locomotives with them, and they had destroyed everything else. Stations, signal installations, bridges and other vital parts of the infrastructure were seriously damaged, sometimes beyond repair.”[162] As the Russians used a unique broad gauge rail system, the Germans had to adapt to continue their advance into Lithuania and Courland; the pre-war training provided to the railway corps was crucial in this task. According to Veenendaal and Grant:

At first the Germans used the existing broad gauge as far as they could. But when their supply lines became longer and longer, they simply had not enough motive power and rolling stock for their transports, and so they began the conversion of the lines to standard gauge. Now German and captured French and Belgian equipment brought over from the west could be used. Hundreds of kilometers of broad gauge were changed into standard gauge. …The rail was absolutely essential in sending supplies to the German armies, hundreds of kilometers into enemy territory.[163]

This process aided Germany greatly in her war on the Eastern Front, allowing her to use converted Russian railways to keep her troops supplied far away from German territory.

Galicia

The Austrians and Russians met early in the war in Austrian Galicia, which bordered Russian territory in Poland. During the war, the Austrians used their army railway (K.u.K. Heeresbahn) to support their advance in Galicia and other theaters; they used their own locomotives, but ran often on public railways that were built to serve civilian traffic.[164] The campaign in Galicia, by both the Russians and Austrians, saw substantial tactical use of railways, especially as roads were few and far between and in very poor condition.[165] According to Veenendaal and Grant, “The front in Galicia fluctuated, with both parties gaining and losing ground. Attackers and defenders both used the railways as much as possible, and when they had to withdraw, both tried to destroy the infrastructure to prevent the other side from using it. Damage was great and difficult to repair.”[166] This front saw heavy fighting, especially in the first months of the war, and most of it revolved around the railways.

Railways through the War

The use of railways during the Great War was constant, impactful, and touched nearly every aspect of the conflict. The rails kept troops supplied, brought them to and evacuated them from the front lines, and were used during battle as tactical supports. They were major targets of sabotage and were involved in direct combat actions. Their impact on the home front was also critical to the war effort. There are four major aspects of railways during the war which deserve deeper study: their logistical impact, the mass use of narrow-gauge field railways, the use and targeting of railways for combat purposes, and the effect on the home front.

Railways and Logistics

Perhaps the greatest role that the railways played during the First World War was that of logistical support. Trains carried nearly all of the goods that would be necessary for warfighting, as maintenance of the vast armies of the war in their entrenched positions required massive amounts of supplies; “Every bullet, blanket, bandage, artillery battery or tin of bully beef had to be manufactured and transported where and when it was required,” a task that – prior to the advent of reliable motorized transport – only railways could handle.[167] According to the Imperial War Museum, “By 1918 each Division of about 12,000 men needed about 1,000 tons of supplies every day – equivalent to two supply trains each of 50 wagons.”[168] This was an absolutely staggering amount of supplies, especially given the fact that all of the belligerents combined fielded several hundred divisions. The armies were not the only military forces requiring supplies, however; the navies also needed supplies including building materials, timber, food, munitions, and the navy’s lifeblood – coal.[169] As the world’s preeminent naval power and an island nation with extensive railways, Britain is an excellent case study in this regard. Before the war, coal was transported to the fleets stationed in the north of England and Scotland by seagoing colliers, but this was halted when the war began due to threats from German U-boats.[170] Therefore, the coal had to be shipped from the mines in Wales to the mustering stations of the fleets, which involved long rail journeys of “375 miles…. [which] generally took something under 48 hours.”[171] These regular trains servicing the British Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in northern Scotland ran every workday from London to Thurso and were called ‘Jellicoe Specials’ after the Fleet’s Commander, Sir John Jellicoe.[172] These ‘Specials’ carried, over the course of the war, “about 2 ½ million tons” of coal to Scapa Flow; the Navy overall consumed about “6 million tons of railborne coal, of which from 80 to 90 per cent came from the steam coal pits in the Rhondda and round Aberdare.”[173] This was an extremely large amount of coal and the predictability of the supplies meant that the Grand Fleet could be ever-ready to confront or bottle up the German High Seas Fleet in the North Sea.

Railways were critical for supporting offensives, as well as moving troops from front to front to support or join in on attacks. This was not a role only embraced by a single power or on a lone offensive; “Every offensive, on both sides, needed thousands of trains to get men, ammunition, equipment, and food and fodder to the required places from where the offensive was going to be launched.”[174] Some of the statistics in this respect are difficult to comprehend in their immense scale. For example, on a single day in 1917, the French military needed more than 100,000 shells for their 75mm field artillery pieces.[175] As the war went on, this only increased; over the last four months of the war in 1918, the French fired more than 272,000 of these 75mm shells on a daily basis, totaling over 32 million shells of that caliber alone.[176] All of these supplies came by rail. The British artillery, during an offensive in June 1917 near Messines, needed sixteen trains of thirty wagons each – solely carrying munitions – every single day.[177] The fact that the railways could keep up with this seemingly insatiable demand for high explosives showcases their paramount role in keeping the war machine churning. Munitions were not the only things that needed moving by rail in advance of offensives: troops needed transport as well. The infamous Baghdad Railway discussed earlier served this purpose during the war: it was a “vital artery for the Turkish and German governments” in their advances and combat in the Middle East.[178] Although it was “of limited military value,” it did “help the Turks to slow down the British advance in Mesopotamia, but only temporarily.”[179] Far more successful was the German use of its European railways to move troops and reinforce its offensives:

With the continuous movements of German divisions from west to east and the other way round, the railway was again of supreme and vital importance. There was no other way of relocating thousands of men with arms and equipment over distances of hundreds, sometimes thousands of kilometers. Complete divisions were transported from the eastern Front to the West, and when necessary, back again to Poland or Byelorussia. …Without the railway, Germany would never have survived the first months of the war.[180]

As the war continued, a new weapon entered the battlefield: the tank. These armored monstrosities were incredibly heavy and cumbersome – as well as unreliable – and therefore could not be brought to the front unless by rail.[181] The British and French, who embraced tanks most assiduously of all the belligerents, developed novel methods of loading and unloading tanks from railways, including special steel ramps which allowed the tanks to drive onto purpose-built wagons that could withstand their enormous weight and bulk.[182] Without the railways to bring them from the factory to the front, tanks may have never played any role whatsoever in the war.

As was to be expected, major issues arose for all of the powers during their attempts to keep the supply lines clear. The Russians, for example, only had two accessible ports – Murmansk and Archangelsk in the north – neither of which was available during the winter, as they were iced over.[183] Besides this natural challenge, the Russians created, through poor planning, artificial hurdles as well. According to Veenendaal and Grant, “the rail lines connecting these towns with the rest of Russia were narrow gauge and single track until 1916 and not in the required shape to transport everything that had landed.”[184] This created serious problems for the Entente in their attempts to resupply their Russian ally by sea, as these desperately needed military goods were unable to reach the armies who required them. The British had their own issues with goods transit, but they were the polar opposite of those suffered in Russia. Instead of being unable to supply their armies due to dearth of railways, the British military used their plethora of railways inefficiently, sending trains with light loads on roundabout journeys which wasted precious coal and time.[185] In an example of this wastage, a single load meant to travel the 247 miles from Edwinstowe to Ashford was routed in such a way that it added 354 miles of excess haulage, more than doubling the cost and time of the journey.[186] This sort of inefficiency was not the only type, as mini-journeys of only a few miles by rail (the shortest on record was a mere quarter-mile) and mini-loads of less than fifty pounds were commonplace in the first years of the war.[187] The British worked this out by the middle of the war, pushing these sorts of decisions away from low-level staff and organizing more rationally.[188]

Railways closer to the front also played a mammoth role in supply and logistics, as did the workers who staffed and ran them so diligently. The British, for instance, increased the number of railway troops they trained for the war from a total of two hundred in 1914 to an astounding sixteen thousand by 1918; these railwaymen worked the British railway system in France, which, by 1915, was fully in British hands (prior to this they were operating on French-run railways).[189] Besides the railwaymen trained specifically for operation of the railways, the British had another sixty thousand railway troops of one sort or another in France in 1918.[190] British railwaymen served in a wide variety of theaters in addition to the Western Front, including “Salonika, Egypt-Palestine and Mesopotamia”[191]; they played crucial roles in all of these areas maintaining, building, and repairing railway infrastructure. The British not only had to supply their own railway workers, they had to ship over locomotives as well, most of which came from the private rail companies who had used them for freight haulage or passenger traffic.[192] As the war dragged on, the British saw the need for a standardized locomotive design that was rugged and could withstand the hardships of the front; they chose a model previously created for the Great Central Railway in 1917 and built more than five hundred for use in France.[193] According to Hamilton, the British used “1660 standard gauge locomotives, of which 951 were sent from Britain, including the requisitioned engines,” during the course of the war.[194] Without these sources of motive power, the logistical challenges posed by the war would have been nigh-insurmountable.

Standard gauge railways were constructed at a fast pace during the war, mostly as a means of supplying the new trench positions on the Western Front; sometimes these required rails used elsewhere on now-quiet civilian lines to be torn up and shipped to the construction zone, as factories were unable to keep up with the demand and prioritized other products like munitions.[195] In Britain alone, over two hundred miles of track were ripped up and shipped to France to be used in the building of strategic supply lines to the trenches.[196] These hundreds of kilometers of newly-built railways could not go all the way to the front lines, “as steam locomotives with their columns of smoke formed too conspicuous a target for enemy gunners. … at night the glare from the firebox could be visible for miles.”[197] The French especially had to reroute and reorganize their railway system, as the infrastructure of the major Nord and Est companies now fell behind enemy lines; these railways, which in peacetime supplied much of France’s coal, were in German hands, forcing the French to ship coal in from farther away.[198] In terms of standard gauge railway infrastructure, all belligerents built new lines, as well as large marshalling yards where supplies and men transported by standard gauge rail could be easily transferred to the narrow-gauge railways which took them the rest of the way to the trenches.[199] Some of this infrastructure is still in use today: the Germans built a new rail line running from Germany proper – the home front – through Belgium to the front lines; it was incredibly well-built and is still used by the Belgian railway system in 2021.[200]

Narrow-Gauge Railways in the War

As stated above, standard gauge railways were unable to reach the trenches directly, having to stop several miles short of the front lines due to the danger posed by enemy artillery past that point. The distance between the standard gauge railheads and the trenches was part of “a wide ‘battle zone’ in which the ground was so shell-torn and fought over that bad weather made it almost impassable”; in the early days of the war, supplies had to be carried on foot over this rough terrain.[201] To solve this problem, all sides developed and used tactical field railways – also known as narrow-gauge railways – to improve and organize supplies and communications with the front lines. These lines were usually on a gauge size of 600 millimeters (60 centimeters or 1 foot 11 inches), and were referred to as ‘two-foot rails’ by the Americans and the soixante by the French. According to the author Steven Trent Smith:

A typical soixante line on the Western Front centered on a terminus, like Sorcy, well behind the front lines and outside the range of most enemy artillery. There standard-gauge trains off-loaded supplies for transfer to the narrow-gauge trains, whose branch lines radiated out to forward sectors. Within the terminus was a workshop for the repair and maintenance of rolling stock.[202]

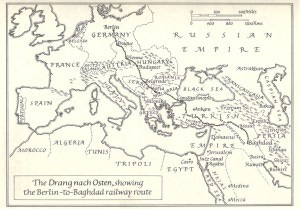

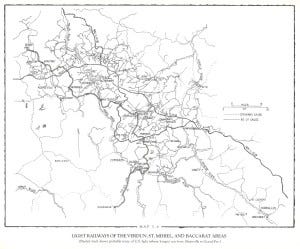

A depiction of the typical layout of a narrow-gauge railway system is shown in Figure III earlier in this post; this image shows the terminus of standard gauge railways at the bottom, the transfer point to narrow-gauge railways just above that, and the branching lines which moved towards the trenches. The image also depicts the limit to where steam engines could no longer operate due to danger from enemy fire – usually at least one mile back from the trench line; at this point, the cargo loads were “rearranged to be forwarded to the front in one or two car trains.”[203] Once reaching the trench line, “goods and munitions moved forward by manpower or horsepower, sometimes on 40 cm tramways running through the trenches. Shells went straight to concealed ammunition dumps, while the daily train of rations trundled farther forward to frontline mess kitchens.”[204] The hundreds of kilometers of narrow-gauge rail lines were complex and came “complete with workshops, sheds, and marshalling yards.”[205] One can see the intricate layout and massive spread of these narrow-gauge lines in Figure IV above; this image shows the web of light railways running to the front in the Verdun, St. Mihiel, and Baccarat areas in northern France, many of which were operated in the later stages of the war by American railway troops.

The narrow-gauge railways were built so rapidly largely due to the ease-of-use of their prefabricated infrastructure. The primary system used by the Allies on the Western Front was the Decauville system, the brainchild of Paul Decauville, a Frenchman who pioneered the use of industrial railways.[206] Decauville’s system of 600-millimeter track was “designed to be portable, quickly laid and quickly replaced in the case of damage.”[207] Veenendaal and Grant detail exactly how the Decauville system worked in practice on the Western Front:

It consisted of sectional pieces of light rail, five meters long with eight steel sleepers and weighing 167 kilograms, portable by four men. Smaller sections were also available, featuring curved sections, crossings, and turnouts. A company of men could lay this track in a short time as long as no great earthworks were necessary. And when a retreat became necessary, the rails could be taken up again and carried back into safety.[208]