The Victorian Cold War

The Great Game and the Eastern Question in the Late Nineteenth Century

Introduction

The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was a global geopolitical, commercial, and strategic conflict which ran from the end of the Second World War in 1945 through the collapse of the USSR in 1991. This long-term, aggressive confrontation between two major world powers without direct military combat was, to many, an unprecedented occurrence which had no major modern historical analogs.[1] Many observers expected the period after World War II to be as rife with conflict as were the years of the first half of the twentieth century, but this was not the case; a number of factors contributed to this, including nuclear weaponry and greater use of diplomacy.[2] “The absence of another great power war was given its name ‘the Long Peace’ by John Gaddis in 1986, a term that endured after the end of the Cold War as this absence continued.”[3] The fact that this period was uncommonly peaceful was both unexpected and welcome; it has been studied for years as a fascinating historical development. But was it a novel historical circumstance at all? If one looks closely, one can find a significant analog just a century earlier.

The second half of the nineteenth century was one characterized by Great Power conflict, but this was not a bipolar world – it was a multipolar one. As communications and transportation technologies were not as advanced at this time, the world was more divided than it would be in the mid-twentieth century. This division, and the competition to “fill up a blank in the map”[4] through exploration, conquest, colonization, and development, led the Powers to compete in more direct ways in a variety of global theaters. These conflicts often crossed the line into warfare, but the story of two of these Powers – Britain and Russia – and their relations in the period from 1856 through 1890 is quite analogous to the Cold War era. Britain and Russia were on very different tracks at this time, as Britain was moving into its period of ‘Splendid Isolation’ while Russia was looking to expand aggressively her sphere of influence across as much territory as she could. The two theaters where these Powers interacted the most were Central Asia and the Balkans; as different as the strategic, economic, and political calculations were for both Powers in these disparate regions, the two areas were firmly interrelated in the minds of their governments. The Eastern Question – as the issue of the Balkans was then called – and the Great Game – the struggle for Central Asia – were essentially two sides of the same coin of geopolitical conflict. Both Russia and Britain found the answers to these questions to be firmly entwined with one another and saw the other Power as an implacable foe across Southeastern Europe and Central Asia. The evolution of the Eastern Question and the Great Game occurred in tandem throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, as events in one area reflected and influenced those in the other. This paper will explore the relationship between Russia and Britain in both regions, how it was dictated by political, strategic, and economic calculations on both sides, and why it never resulted in direct military conflict. The focus of this paper will be on the British side of the ledger, but Russian motives and decisions must be discussed to properly understand those of the British.

The Context

Before delving into the particulars of the motivations and strategies of the British against the Russians in Central Asia and the Balkans, we need to fully understand the geopolitical and historical background behind them.

Geopolitics: Central Asia and Southeastern Europe

Geographic considerations were at the heart of the Anglo-Russian competition in the nineteenth century. We must see the fascinating provinces of Central Asia and Southeastern Europe through the eyes of the intrepid explorers, canny diplomats, ambitious politicians, and belligerent soldiers who played such crucial roles in their history over the course of the latter half of the nineteenth century. This era was one of dramatic and historic change for both Central Asia and the Balkans; the famed British politician and imperialist Lord George Nathaniel Curzon said of this epoch in Central Asia that:

It is the blank leaf between the pages of an old and a new dispensation; the brief interval separating a compact and immemorial tradition from the rude shock and unfeeling Philistinism of nineteenth-century civilization. The era of the Thousand and One Nights, with its strange mixture of savagery and splendour, of coma and excitement, is fast fading away, and will soon have yielded up all its secrets to science. Here, in the cities of Alp Arslan, and Timur, and Abdullah Khan, may be seen the sole remaining stage upon which is yet being enacted that expiring drama of realistic romance.[5]

These words capture the feelings of the British government and populace towards the unconquered domains of Central Asia, and it is worth exploring the region which so inspired them and which hosted the playing field of the Great Game.

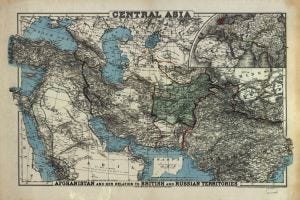

According to historian Peter Hopkirk, “The vast chessboard on which this shadowy struggle for political ascendancy took place stretched from the snow-capped Caucasus in the west, across the great deserts and mountain ranges of Central Asia, to Chinese Turkestan and Tibet in the east.”[6] This region can be seen below in both Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is a broad map of the entire theater of operations which will be discussed in this paper and covers both Central Asia and Southeastern Europe. Figure 2 shows the Central Asian ‘playing fields’ of the Great Game, centering on the key country of Afghanistan and the approaches to India – these were the primary focuses of the British. Between these two maps, published in the mid-1880s, one can see the general geopolitical organization of the region. Geographically, Central Asia is replete with high-altitude mountain ranges with a few key passes, vast deserts with little in the way of resources, and crucial waterways that connect and divide the region. This rugged territory was fairly poorly mapped at the time, given the lack of aerial imaging and the impenetrability of many of these remote locales. Politically, the maps show the Russian and British territories as of 1886 – the areas controlled by the Russians expanded rapidly in the three decades after 1856, while the British largely kept their annexations to what are now modern India and Pakistan. The Great Game was played out in the middle ground between these two powers, which historian Evgeny Sergeev breaks down into three political clusters: “large, ancient states, such as China, Persia and Afghanistan; medieval khanates and emirates, such as Khiva, Bokhara, Khokand, Kashmir, and Punjab; and proto-state tribes and communities occupying the so-called no-man’s-lands.”[7] To the British, the essential issue was the protection of her jewel of a colony in India, which meant that the approaches to that land were of paramount importance. In the period from 1856 through 1890, the most important locations in this respect were Afghanistan, the khanates of Khiva, Bokhara, and Khokand, and the eastern reaches of Persia. Afghanistan itself deserves further scrutiny, especially the critical Bolan and Khyber Passes through the Hindu Kush mountains and into British India, as well as the cities of Herat, Kabul, and Kandahar. These mountain ranges are “pierced by many highways through which, from time immemorial, foreign invaders had swooped down upon the plains of the Indus Valley.”[8] The importance of the passes is self-evident, as it would be impossible to mount an invasion force over these enormous peaks. The cities of Afghanistan were equally as vital and played a heavy role in guarding the routes to India. Kabul, besides being the capital of Afghanistan, is situated near the Khyber Pass; Kandahar, further to the south, is at the foot of the Bolan Pass. Kandahar especially is located in a relatively flat area in which troops would have been able to stage further incursions into the British sphere of influence. Herat, which is in the far western reaches of Afghanistan, was on a direct line of march to Kandahar; this, along with Herat’s natural advantages of fertility and climate, made that city “both strategically and politically an indispensable bulwark of India.”[9]

With respect to the geography of Southeastern Europe, there are two major areas – connected by an important thread – which matter to our story: the Balkans and the series of straits in the Eastern Mediterranean. These areas are linked by their connection to the ‘Sick Man of Europe’, the Ottoman Empire. In 1856, the Ottomans were already on the ropes, but would hang on to life for another sixty-two years; their hold over the Balkans would end far sooner than that. The Balkan developments which led to the collapse of Ottoman Europe will be detailed later, particularly the British and Russian strategic elements related to that fall. It is nonetheless useful to gain a picture of this turbulent region as of the end of the Crimean War. Ottoman power was being pushed back by the Concert of Europe, just as the fiery nationalisms of the Balkans were being birthed. The Balkans were a hotbed of ethnic difference, from Bosnians, to Serbs, to Bulgarians, to Romanians. All these peoples were agitating for their own national independence, even if under the temporary, nominal control of a power like Russia or Austria – the two major European players in the region. By 1856, as one can see in the map of the Balkans below (Figure 3), Turkey regained control over much of the region, but this was a fleeting victory. The other aspect of this region which mattered to the British was the Eastern Mediterranean, which can be seen in Figure 1. This area was home to three crucial waterways which the British needed to ensure clear communications and commercial ties between the disparate outposts of her Empire: the Bosporus, the Dardanelles, and the Suez Canal. The Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits were both held by the Ottoman Turks and controlled access from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara at Constantinople and thence to the Mediterranean. As the British sought to enforce their hegemony over the Mediterranean, controlling the access points from the Black Sea – and thus keeping Russia contained therein – was of supreme importance.[10] As time went on, British interest in the Eastern Mediterranean increased, as it was seen as a crucial link to Britain’s far-off colonies. Historian J.A.R. Marriott argued that “It is doubtful whether any single event in world-history, since the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, did more to influence the orientation of British policy than the opening (1869) of the Canal through the isthmus of Suez.”[11] This canal “reduced the distance by sea between Britain and India by some 4,500 miles,”[12] and became “a symbol of the demand for quicker transit between the center and the periphery.”[13] British eyes focused even more heavily on these regions after the Crimean War, a conflict which set the stage for the next fifty years of Anglo-Russian relations.

History: The Crimean War and the Treaty of Paris

The event which sparked the next half-century of Anglo-Russian Cold War was the Crimean War and that conflict’s conclusion with the Treaty of Paris of 1856. These three years of combat and negotiation would fundamentally reorient the nature of the fight between the British and Russians for dominance in the Balkans and Central Asia. The British statesman Lord Cromer put the historical importance of the Crimean War and its aftermath quite well, saying “Had it not been for the Crimean War and the policy subsequently adopted by Lord Beaconsfield’s Government, the independence of the Balkan States would never have been achieved, and the Russians would now be in possession of Constantinople.”[14] The leadup to this war and its conduct is beyond the scope of this analysis, but suffice it to say that regardless of the initial casus belli, the war “became a conflict between Russian attempts to control the Turkish government and British fears of Russian expansion.” The end of this slog of a war came with the Treaty of Paris in 1856; the British emerged from these negotiations victorious, while the Russians were forced to retreat and lick their wounds. According to the historian A.J.P. Taylor, “The treaty ‘solved’ the problem of relations between Russia and Turkey in three ways: the Turks gave a voluntary promise to reform; the Black Sea was neutralized; the Danubian principalities were made independent of Russia.”[15] In British eyes, “The provisions of the peace treaty were designed to give Turkey all the necessary means of resisting Russian aggression in the future,” from the neutralization of the Black Sea, to the strengthening of Turkey’s borders, to the European guarantee of the “independence and integrity of the Ottoman Empire.”[16] Of all these advantages which were granted her by the Treaty, the Ottomans “did not avail themselves.”[17]

The war, although nominally fought to protect and preserve Turkey, was mostly an anti-Russian affair[18]; that nation fared worst in the outcome of the treaty negotiations. The British “regarded Russia as a semi-Asiatic state, not much above the level of Turkey and not at all above the level of China,”[19] and dealt with her accordingly – by working to strip her of “almost everything she had laboriously obtained by a century of consistent diplomacy and several wars: to thrust her back from Constantinople; to repudiate her quasi-protectorate over Turkey; and to close the Black Sea to her ships of war.”[20] Although the Russians suffered a severe setback in the Crimean War, her “ambitions in the Balkans and the Black Sea were not destroyed.”[21] In fact, Russia would continue her intrigues in this region for the next sixty years, culminating in the first World War. The Crimean War significantly harmed Anglo-Russian relations, destroying any positive memories of alliance in the Napoleonic era.[22] Both sides grew in animosity towards the other, even as the British came away triumphant from Paris in 1856, and “Political opposition between the two nations became inveterate.”[23] Going forward, however, Russian intrigues in Europe were calculated to ensure that she would not again run up against the British directly. To this aim, Russia looked to the east, specifically to Central Asia. Sir Henry Rawlinson, reflecting a good deal of British popular opinion, claimed in 1875 that Russia’s Asian strategy was “the deliberate action of a government which aims at augmented power in Europe through extension in Asia.”[24] Indeed, “The majority of the British public concurred in the pessimistic opinion that the Russians ‘sought to besiege Constantinople from the heights above Peshawar.’”[25] As we will see, this feeling was not unjustified, and it drove the next fifty years of Anglo-Russian conflict across the Balkan and Central Asian theaters.

The Political Question

There are three political aspects to this Victorian Cold War which are worth exploring; the most important is the issue of internal British politics, while Russian political factors and the nature of politics on the frontier of Empire are also pertinent. With respect to British politics, the major factor was the fight between the Conservative and Liberal governments of the time, especially those of Prime Ministers Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone. These two men and their opposing philosophies drove the politics of the latter half of the nineteenth century, even after Disraeli himself died in 1881. Their differences with respect to domestic politics were myriad, but their foreign policies were just as diametrically opposed, especially when it came to the issue of Russia. Author John Lowe describes Gladstone’s foreign policy as:

…idealism rampant, combined in a curious way with a strong legalistic vein. Foreign policy ought not to be about the pursuit of power, he believed, but the rule of law applied to international affairs. Gladstone also displayed a touching belief in the Concert of Europe as a mechanism for realising the new era in international affairs that he naively believed possible in an age characterised by Realpolitik. [26]

Gladstone’s administrations were typified by fiscal retrenchment, which sapped the budget of the British military – especially the expensive Navy – and dovetailed with his lack of interest in asserting Britain’s Great Power status.[27] In terms of the questions of Central Asia and the Balkans, one could call Gladstone and his Cabinets firmly Russophilic as well as Turkophobic; these two attitudes were often linked, as the Russians and Turks were constantly in conflict during this period. The opinion of the Liberal Party was obvious to all observers, domestic and foreign. Indeed, one contemporary writer declared that “Mr. Gladstone’s Cabinet is notoriously given to making concessions, and Russia, well aware of this, is resorting to every artifice to squeeze it.”[28] This affinity for the Russians, combined with Gladstone’s distaste for direct confrontation, led him and the Liberal Party to pursue more defensive policies and work towards international agreements to resolve thorny geopolitical issues in the Balkans and Asia. Gladstone’s nemesis, Benjamin Disraeli, was a fascinating political figure who was almost the polar opposite of Gladstone; his Conservative foreign policy was imperialist, aggressive, and realpolitik-driven. Lowe claims that “Disraeli was no idealist. He was an opportunist, pursuing whatever policy seemed expedient at the time, with an eye to prestige successes.”[29] He was also far more militaristic than was Gladstone, an attitude exemplified by his famed Guildhall Speech of November 9, 1876, in which he directed towards Russia the following sentiment:

Although the policy of England is peace, there is no country so well prepared for a war as our own… If she enters into conflict in a righteous cause…if the contest is one which concerns her liberty, her independence, or her empire, her resources, I feel, are inexhaustible. She is not a country that, when she enters into a campaign, has to ask herself whether she can support a second or third campaign. She enters into a campaign which she will not terminate till right is done.[30]

This attitude was not only meant to expand the British Empire, but was also a driver of greater involvement in the affairs of Europe; the historian R.W. Seton-Watson writes that “Thanks to [Britain’s] strong colonial and naval position, nothing could happen outside Europe without [her]: and Disraeli wished this to be true of Europe also.”[31] He was eminently aware of the importance of Great Power politics and relations, something which Gladstone never seemed to fully appreciate.[32] Disraeli and the Conservative Party more broadly were Russophobic and thus also Turkophilic; when his administration took over from Gladstone’s in 1874, forward policies in Asia returned and Anglo-Russian relations became significantly worse.[33] Disraeli was a strong supporter of the Sublime Porte and “not only stubbornly upheld the Palmerstonian doctrine of Turkish independence and integrity, but clung to every favourable verdict upon Turkey and gave his support to Turkey wherever he could.”[34] Any analysis of this era of British politics would be incomplete without mentioning the attitudes of the nation’s monarch, Queen Victoria. The Queen was firmly in the Disraelian camp when it came to foreign policy, especially when it came to relations with Russia; she was even said to have spoken on various occasions of “laying down the Crown rather than ‘kiss[ing] Russia’s feet.’”[35] Victoria had what some called “a Russophobe obsession,”[36] and once stated to the Prince of Wales that “I don’t believe that without fighting…those detestable Russians…any arrangements will be lasting, or that we shall ever be friends! They will always hate us and we can never trust them.”[37] In her Russophobia, the Queen even sometimes went too far for her favorite minister’s tastes, but he humored her regardless.[38]

The other political factors which bear mentioning are the affairs of the Russian Court and the unique nature of frontier politics for both the British and the Russians. Russian politics revolved around the person of the Tsar, as he was a nominally autocratic ruler during the latter half of the nineteenth century. The advisors around the Tsar did prove influential, as we will see with respect to the ideology of Pan-Slavism, but the man on the throne was the critical player. He could – and did – dismiss his advisors at will, and often changed tack based on personal whims. The hereditary nature of the throne made policy continuity a low priority; legitimacy for the Tsar was most important. Fathers and sons were sometimes entirely opposed in terms of policy. For instance, “The change of rulers from Nicholas I to Alexander II produced a change of atmosphere in the national life that has been likened to the sudden advent of spring after a long Russian winter…the imposing reign of a despotic sovereign ended in humiliation and reaction from absolutism.”[39] Nicholas I, the keeper of the reactionary flame in Europe, was replaced by a son – Alexander II – who emancipated the serfs. The other political consideration to understand with respect especially to Central Asia is that the nature of frontier politics in the nineteenth century did not lend itself well to control by faraway central governments. Before the turn of the twentieth century, communications and transportation infrastructure was developing rapidly – railroads, telegraphs, and road networks all grew in this era – but the remote playing fields of the Great Game were relatively untouched by these technologies. In fact, the laying of rail lines in Central Asia during the late-nineteenth century became a major point of contention between Britain and Russia and almost led to war. In the absence of these technologies, communication was quite challenging and orders could not be delivered in timely fashion to those at the frontiers. Even as the crow flies, St. Petersburg was over two thousand miles away from Tashkent, the capital of Russian Turkestan and a key city in the Great Game, while London was over four thousand miles from her Indian base at Simla; this made it all but impossible to exercise any sort of real central control over policy implementation in Central Asia. Therefore, the leaders on the ground were granted a great deal of autonomy. Policy was often improvisational; this was the case for Russian generals and British subalterns alike. One example is the June 1865 capture and annexation of Tashkent by the Russian general Mikhail Cherniaev, which he undertook without the express authority of the Tsar; Cherniaev figured that “once the imperial flag had been raised over Tashkent the Tsar would be loath to see it hauled back down,” and he was correct in that assertion.[40] In the words of Evgeny Sergeev, Cherniaev “acted on his own will in the manner he considered most suitable for current circumstances – like a Tsarist conquistador”[41]; this was not at all out of the ordinary for the period in question. The only way to tamp down this common attitude among the most advanced players of the Great Game was to install someone locally who was powerful enough to exercise a greater degree of control; these Governor-Generals and Viceroys often made and implemented their own policies in Russian Central Asia and British India, respectively. For the British, Viceroys came and went with changes in the political situation back home; as we have seen, the Liberals of Gladstone and the Conservatives of Disraeli radically differed on India policy and their handpicked Viceroys reflected these disparate views. Disraeli, after winning the 1874 election, selected the aggressive Lord Lytton as Viceroy to replace Gladstone’s man Lord Northbrook, who was too passive for the new Prime Minister’s tastes[42]; Gladstone returned the favor in 1880 by replacing Lytton with Lord Ripon, who pledged to totally overturn the prior administration’s policies.[43] For the Russians, Governor-Generals were granted even greater autonomy than were the British Viceroys; the Governor-General of Russian Turkestan from 1867 through 1886, Konstantin Kaufman, was granted enormous powers by the Tsar. “His plenary powers were so formidable – the tsar delegated to him full political, military, and financial authority for the conquered territories – that local nationals called him the ‘semi-tsar’.”[44] These political factors, at the center and the periphery of the Russian and British empires, played a major role in the unraveling of the Eastern Question and the acceleration of the Great Game.

The Eastern Question Answered?

The Eastern Question evolved after the Crimean War, eventually regaining primacy in European affairs in the mid-to-late 1870s before it reached a new equilibrium which lasted almost through the first World War. Although the specific events of this period deserve some explication and examination, the implications for British and Russian strategy, politics, and commerce were far more profound. The major cluster of events which nearly sparked war between the two Powers – the Bulgarian atrocities, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 to 1878, and the Congress of Berlin – were both influenced by and influences on British and Russian geopolitical strategies. Before diving into these turbulent waters, we must understand the evolution of the Eastern Question and the interests of the Powers in Southeastern Europe.

One of the major issues which specifically impacted the Russian understanding of the Eastern Question was the doctrine of Pan-Slavism, which dominated Russian intellectual circles after the Crimean War.[45] “This mixture of western nationalism and Orthodox mysticism varied in practice from vague Slav sympathy to grandiose plans for a united Slav empire under tsarist rule; the sentiment, not the programme, was the important thing about it.”[46] This doctrine was promulgated by popular writers “including the great novelist Fëodor Dostoevski and the publicist N.I. Danilevsky,”[47] and it had strong public support. Many of the key advisors to Tsar Alexander II – including N.P. Ignatiev, his ambassador to Constantinople – “were themselves inclined to Panslavism and eager at any rate to exploit it.”[48] During this time, Pan-Slavism – in its full Romantic glory – was not implemented as government policy, but was instead used “by the Russian government only as a mask for Russian imperialism.”[49] As Southeastern Europe, especially the Balkans, was inhabited mostly by Slavic populations, this region was a prime target for Russian Pan-Slavist agitation; it was surely not a coincidence that this would put them at odds with the Ottomans and bring them one step closer to the Straits.

The question of the Straits was the prime driver of British opinion with respect to the Eastern Question during the run-up to the events of the mid-1870s. Since the triumph of the British delegation at Paris in 1856, the Russians had slowly been chipping away at the hated Black Sea provisions of the Treaty. Alexander Gorchakov, the Russian Foreign Minister from 1856 through 1882, once said to a subordinate that “I am looking for a man who will annul the clauses of the treaty of Paris, concerning the Black Sea question and the Bessarabian frontier; I am looking for him and I shall find him.”[50] Gorchakov succeeded in his quest to alter the 1856 settlement; Russia officially denounced the neutralization of the Black Sea to the other Powers of Europe in October 1870[51], causing “indignation in Turkey and in Britain, but little interest elsewhere.”[52] This unilateral modification of a multilateral treaty was mostly a symbolic gesture, as the Russians did not actually build a Black Sea fleet; the response of the Gladstone government was equally as symbolic, as they pushed for an international conference to adjudicate the matter.[53] The London Conference of 1871 seemed at the time to be a British capitulation, as she allowed the changes the Russians desired, but it would come to good use only seven years later at a more well-known conference of the Great Powers.[54] These modifications worried the British public, as many saw the Straits as the key to the British Empire; a rival’s control over the eastern Mediterranean would cut the supply lines from India coming through the Suez Canal. That canal, strategically and economically crucial to the Empire, became even more so after 1875. In November of that year, Disraeli executed a political and foreign policy masterstroke by purchasing a controlling interest in the Suez Canal from the financially-strapped Khedive of Egypt.[55] This secretive purchase was driven largely by British apprehension over Russian designs on the Straits; “Disraeli wished to make absolutely sure that this crucial lifeline, for both troops and goods, could never be threatened or even severed by a hostile power.”[56] The feeling of British imperialists in the late 1870s was one of uneasiness, especially over the issue of the Straits. This was captured by Colonel Sir Henry Havelock, MP, in his 1877 article ‘Constantinople and our Road to India’, which he concluded with an ominous warning over the Straits: “Once astride on the Dardanelles, instead of being ‘nothing to us’, Russia has us by the throat, and it only requires the pressure of her iron fingers in a tightened grip of the windpipe to strangle our commerce in three months.”[57]

This prediction almost came true only a few months after it was issued, as the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 to 1878 was a devastating defeat for the Ottomans and a stunning victory for the Russians. This war was essentially a redux of the Crimean War of twenty years earlier, but without the participation of the British or French; it revolved around the Balkans and the Straits, and was triggered by what came to be known as the Bulgarian Atrocities. These slaughters were carried out by irregular Turkish troops in their Bulgarian possessions in Europe, and involved mass murder and rape of Christian civilians in large numbers.[58] The reaction to these killings in British politics was mixed; Disraeli and his Conservative government wanted to preserve Ottoman control in Europe and so reacted mildly, but Gladstone and the Liberals had no such compunction.[59] In his famous pamphlet, ‘Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East’, Gladstone suggested what he saw as the only reasonable solution, and one which had significant public support:

Let the Turks now carry away their abuses in the only possible manner, namely by carrying off themselves. Their Zaptiehs and their Mudirs, their Bimbashis’ and their Yuzbachis, their Kaimakams and their Pashas, one and all, bag and baggage, shall, I hope, clear out from the province they have desolated and profaned.[60]

Given the Pan-Slavist bent of the Russian regime, these horrors were used as a casus belli against the Turks. Her armies – along with those of other opportunistic Balkan states like Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania – pushed the Turks back into Asia and settled on the doorstop of Constantinople.[61] The resulting Treaty of San Stefano “would have virtually put an end to the Ottoman Empire in Europe,” as it created a large Bulgaria which spanned from the Black Sea to the Aegean, possibly “outflanking the Straits and making the whole of the Balkans a Russian protectorate.”[62] San Stefano was the apex of the Pan-Slavist dream, but it was not to last; the Russian overreach moved British public opinion towards siding with the Turks against her ‘persecutors’.[63] British warships were sent to the Straits and a vote of war funding was asked of Parliament.[64] Many in the British public wished for war and felt ready for it; a popular song of the time went “We don’t want to fight, But by Jingo if we do, We’ve got the men, we’ve got the ships, We’ve got the money too. We’ve fought the Bear before, And, if we’re Britons true, The Russians shall not have Constantinople.”[65] The lyrics referenced Disraeli’s Guildhall speech, and the Prime Minister himself shared many of their sentiments; still, he knew that Britain was not prepared for a major war with Russia and so “only meant to scare the Russians and assert British prestige by a piece of bluff.”[66] Russia fell for this ruse and agreed to submit the Treaty of San Stefano to a European conference; the Congress of Berlin opened on June 13, 1878 and lasted one tumultuous month.[67] At its conclusion, the map of the Balkans was redrawn, the Russians returned home largely unhappy, and Disraeli was feted in London; Chancellor Otto von Bismarck summed up the Prime Minister’s performance simply, saying “Der alte Jude, das ist der Mann.”[68] The geopolitical changes wrought by the Congress can be seen in Figure 3, but those were not the only legacies of the meeting. Britain gained a foothold in Cyprus, through which she hoped to cement her hegemony over the Eastern Mediterranean and protect her interests in Egypt.[69] Russia accepted the new normal in the Balkans and focused on turning these new states to her advantage – with mixed results.[70] The biggest legacy of the Congress with respect to the Eastern Question was that after it was over, “both Britain and Russia…had lost much of their interest in Turkish affairs. … The Eastern Question was not dead. But circumstances were now entirely altered, and the very name had become an anachronism.”[71]

The Great Game’s Final Innings

Once the Eastern Question had been answered, the eyes of the British and Russians turned firmly to the East; Central Asia and the playing fields of the Great Game exploded with activity. To this point in time, the strategies of the two Powers were divergent, with Britain focusing on reinforcing the borders of India and establishing a sphere of influence over border states and Russia inexorably marching forward, annexing all who stood in her way; according to the writer Alexis Sidney Krausse, “The history of Asiatic Russia is a record of uninterrupted conquest and absorption extending over a period of more than three centuries.”[72] Over the decades just prior to the Congress of Berlin, Russia captured such major cities and khanates as Tashkent (1865), Samarkand (1868), Bokhara (1868), Khiva (1873), and Khokand (1875)[73]; their steady advance south and east from their bases on the shores of the Caspian was primarily military in nature, but was followed by Russian traders and goods. As the strength of the Russian position in Asia improved, that nation would have the ability to take a higher tone in European disputes[74]; indeed, “Russian expansion across Central Asia in the 1860s and 1870s was in part a response to the setbacks in the Near East in 1856.”[75] Fairly soon after her conquest of Tashkent, Russia began to look into more rapid means of transit from her European bastions to this new territory in Asia; as she advanced into Trans-Caspia – the region to the east of the Caspian Sea – the idea of a railway became more realizable.[76] The laying of tracks began in the years after the Congress of Berlin and connected most of Russia’s Central Asian territories. This railway “across the Trans-Caspian deserts would be the easiest and quickest means of connecting these possessions with European Russia… [and] would therefore be of great political and economic, as well as military, value.”[77] The military import of this railway was excellently described by the German writer and Russophile Józef Popowski: “Now that Russia has crossed the Turcoman desert, acquired the fertile oases south of the latter, and completed the Trans-Caspian Railway, she is in a position to concentrate large masses of troops on the Afghan frontier.”[78] The British saw this logistical encroachment as both a geostrategic and a commercial danger; Lord Curzon, writing on economics, thought that the railway possessed “a commercial future of the very first and most serious importance,” and could lead to Russia becoming “a more formidable antagonist to [British] mercantile than to her imperial supremacy in the East.”[79] British opinion was decidedly negative when it came to Russian railways; Major-General Edward Cazalet stated that “The construction of these routes will be a most fatal and conclusive blow to England on the part of Russia.”[80] The Russian expansion in the decades after the Crimean War, accelerating post-1878, showed the differences in the British and Russian strategies with respect to Central Asia; this is exemplified in the case of Afghanistan.

As we have seen, the Russian approach to expanding and protecting her interests in Central Asia was accomplished via territorial conquest and annexation; her domains proliferated and it seemed to observers “that the continued advance of Russia in Central Asia is as certain as the movement of the sun in the heavens.”[81] The British, on the other hand, focused far more on entrenching her dominance of India proper and establishing a sphere of influence over India’s neighbors through a ‘buffer state’ policy. In international relations, “any buffer state might be regarded as territory that separated two rival or potentially hostile great powers for the preclusion of armed conflicts”[82]; this was an old concept for Europe, but the Great Game was the first time it was applied to non-European theaters.[83] In this instance, Afghanistan “as an independent state, could act as a buffer between the expanding Russian empire and British India.”[84] This system of protectorates allowed the British to keep their governance footprint light and outsource the first line of territorial defense of India to other parties; still, it was a costly scheme, as “enormous sums” were spent by Britain “in fortifying the independence of Afghanistan.”[85] Compared to the cost of military action, this was a bargain.

British India policy over the second half of the nineteenth century fluctuated with political changes back in London; the two major schools of thought when it came to this issue were the Forward policy and ‘Masterly Inactivity’ – the former a Conservative favorite, the latter the domain of Gladstone’s Liberals. The concept of ‘Masterly Inactivity’ was a pacifistic version of the buffer state theory; “The real meaning of this phrase, as interpreted by the action of those who adopted it, was that Russia might do as she pleased in Central Asia, provided she did not touch Afghanistan; whilst British India should remain inactive.”[86] It seemed for a while that Russia concurred. As the Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov said to his Ambassador in London, “we regard Afghanistan as lying outside the sphere wherein Russia exercise her influence. Any intervention or encroaches upon the independence of this state is inconsistent with Russia’s interests.”[87] This reassuring statement was belied by Russian actions in the region, as she continually pushed towards Afghanistan’s borders, annexed disputed areas, and sent envoys to the Afghan ruler. These actions were seen by the proponents of the Forward School as discrediting the theory of ‘Masterly Inactivity’. The Forward School, when it was initially posited in the mid-nineteenth century, was a more militarized policy of “bringing into subjection not only the tribesmen of the Himalayas, but Afghanistan and Baluchistan”[88]; it evolved over time into the more politically-focused idea of “advancing the frontiers with the aid of strategic railways and establishing British influence over regions such as Afghanistan.”[89] Sir Henry Rawlinson, the famed disciple of the Forward School, put it simply when discussing how Britain should respond to continued Russian pressure on the Afghan frontier: “if she deliberately threw down the gauntlet, she must expect it to be taken up.”[90] Over time, the two diametrically opposed strategies were undercut by events on the ground; the Russian advances made a mockery of ‘Masterly Inactivity’, while the failures of the First and Second Anglo-Afghan Wars put the lie to aggressive forward action. Instead, there was a new convergence of policy around the idea of “a Buffer Afghanistan, independent though subsidised, and friendly though strong.”[91] This theory was a synthesis of the two schools of thought, as it took the theoretical underpinnings of the Forward School – that Russian advances needed to be checked by British action – and combined them with the more cautious, diplomatic methods of ‘Masterly Inactivity’.

This new synthesis found its highest expression in the late-nineteenth-century idea of a ‘Scientific Frontier’; this was defined as “a Frontier which unites natural and strategical strength.”[92] In the case of Afghanistan, her mountainous terrain was the key to India’s western border; “by placing both the entrance and the exit of the passes in the hands of the defending Power, [this] compels the enemy to conquer the approach before he can use the passage.”[93] To implement this theory, the British took certain outposts on the Afghan side of the Hindu Kush and Himalaya Mountains, such as Quetta, and fortified them against potential Russian attack. Britain also expanded her construction of strategic railways to link the heart of India with her frontiers, so as to accelerate possible troop movements to the front.[94] The new theory of Indian defense was applied to the borders of her buffer state in Afghanistan as well. The British wished to cement Afghanistan’s western boundaries against the increasing Russian tide, which resulted in the infamous Penjdeh Incident of 1885, where Russian and Afghan troops exchanged fire in a disputed region which touched the Afghan, Persian, and Russian frontiers.[95] This event was seen in Britain as the long-awaited Russian incursion towards India and it set off a series of war preparations and threats, even though the Liberal administration of Gladstone was generally seen as pacifistic. The calling out of the British Reserves and the vote of an eleven-million-pound war credit in Parliament eventually amounted to no more than belligerent words[96]; both Powers agreed to a boundary commission over the Penjdeh region which settled the affair after years of negotiation.[97] The end result was a more stable frontier between Afghanistan and Russia, with the Russians holding Penjdeh and the Afghans receiving the vital Zulfikar Pass[98]; this settlement can be seen in Figure 4, which shows the view from western India, over Afghanistan, to Russian territory. The image depicts the clear importance of the mountain ranges and passes to the defense of India’s ‘Scientific Frontier’, and shows the true ‘buffer’ status of Afghanistan as of 1890. After the agreements of the Boundary Commission, “a kind of fragile equilibrium between Russia and Britain had been established,” as “both empires arrived at a strategic stalemate at the culmination point of the Great Game.”[99] Over the next three decades, Anglo-Russian competition receded in the face of a new mutual threat – the German Empire – and this Cold War had its denouement, ending in the Triple Entente.

Conclusion

Overall, the relationship between Britain and Russia from the end of the Crimean War through the demarcation of the Afghan boundaries was one which closely resembled a ‘Victorian Cold War’. Both Great Powers had competing interests – political, strategic, and commercial – across distinct parts of the globe, especially in Southeastern Europe and Central Asia. The two nations saw their interests and policies in these areas as intricately related and primarily oriented against the other. The Russian joint strategy was expressed by her Viceroy of the Caucasus, Prince Alexander Dondukov-Korsakov, when he sent memos to the Tsar stating that “Russia should deliberately play the role of a formidable power in the East, pressing England to be more compliant in other regions of the world, and above all, in Europe.”[100] The Russians strongly desired a warm-water port, particularly through control over the Straits; they saw this goal as achievable through putting pressure on her rival Britain’s Achilles Heel: India. They wished to expand their holdings in Central Asia for the purpose of opening new exclusive markets for Russian goods, accessing raw materials for industry, and securing Russia’s southern flank from unstable semi-states and tribes.

British opinion agreed with Russian when it came to the latter’s motivations in Asia and their connection to the European theater. In his typical literary prose, Lord Curzon explained this idea:

The Parthian retreated, fighting, with his eye turned backward. The Russian advances, fighting, with his mind’s eye turned in the same direction. His object is not Calcutta, but Constantinople; not the Ganges, but the Golden Horn. He believes that the keys of the Bosphorus are more likely to be won on the banks of the Helmund than on the heights of Plevna. To keep England quiet in Europe by keeping her employed in Asia, that, briefly put, is the sum and substance of Russian policy.[101]

As the British saw their interests in Central Asia as directly related to their interests in Southeastern Europe, they mirrored the Russians in policy terms, pushing back against the Tsar’s forces when they were themselves pushed upon. The increased importance of the Suez Canal for transit to and from India made control over the Eastern Mediterranean a must for Britain; still, keeping these sea lanes open was only useful if India itself were protected from land-based attack. These imperial considerations were part and parcel of the same idea: India – and the links from that colony to the metropole in London – must be kept secure. The British did not wish to achieve this objective through force, but instead through a carefully-considered policy of buffer states and diplomatic conferences which would serve her needs while reducing the cost of Empire. These facts make the period from the end of the Crimean War through the Afghan boundary settlement a great deal like the twentieth-century Cold War; both powers saw the other as an implacable rival worldwide, each made their share of aggressive moves and defensive responses, both had a mixture of interests – commercial, strategic, and political – to protect and advance, and there was never direct armed conflict between the two powers – despite the myriad proxy wars and related conflicts which broke out. By looking at the relationship between Russia and Britain in the latter half of the nineteenth century through the joint prisms of the Great Game and the Eastern Question, one can see how this Victorian Cold War evolved, played out, and ended with a mutual truce. Without the clarifying events of the post-Crimean War era, it is doubtful that the British and Russians would have joined together to face the broader threat of a rising Germany; to this, the statesmen of the First World War would owe a debt of gratitude.

Bibliography

Aldous, Richard. The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone vs. Disraeli. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.

Cawston, George and Edward Stanford Ltd. The Eastern Question in Europe and Asia. 1886. Map on linen, 42 cm x 68 cm (16.54 in x 26.77 in). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7420.ct003773.

Curzon, George N. Frontiers. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1907. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433082424254&view=1up&seq=9.

Curzon, George N. Russia in Central Asia in 1889 and the Anglo-Russian Question. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1889.

De Worms Pirbright, Henry. England’s Policy in the East. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. https://archive.org/details/englandspolicyi00pirbgoog/page/n6/mode/2up.

Freedman, Lawrence. “Stephen Pinker and the long peace: alliance, deterrence and decline.” Cold War History 14, no. 4 (2014): 657-672. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2014.950243.

Ghose, Dilip Kumar. England and Afghanistan: A Phase in Their Relations. Calcutta: The World Press Private Ltd, 1960.

Gladstone, William Ewart. Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1876. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bulgarian_Horrors_and_the_Question_of_th/ipQDAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover.

G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. Central Asia: Afghanistan and her relation to British and Russian territories. 1885. Map, 45 cm x 77 cm (17.72 in x 30.32 in). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7210.ct001160.

Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. New York: Kodansha Globe, 1994.

John Bartholomew & Company. Changes in Turkey in Europe 1856 to 1878. 1912. Map, dimensions unknown. Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/balkans_1912.jpg.

Krausse, Alexis Sidney. Russia in Asia: A Record and a Study, 1558-1899. Leiden: Global Oriental, 2012. E-Book.

Lowe, John. Britain and Foreign Affairs 1815-1885: Europe and Overseas. London: Routledge, 1998. E-Book.

Malleson, G.B. The Russo-Afghan Question and the Invasion of India. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1885. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t9v12007h&view=1up&seq=7.

Marriott, J.A.R. Anglo-Russian Relations 1689-1943. London: Methuen & Co., 1944.

Middleton, K.W.B. Britain and Russia: An Historical Essay. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1971.

Payne, W.H. Letts’s Bird’s Eye View of the Approaches to India. 1900. Map, 49 cm x 72 cm (19.29 in x 28.35 in). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7631a.ct002013.

Popowski, Józef. The Rival Powers in Central Asia or The Struggle Between England and Russia in the East. Translated by Arthur Baring. Edited by Charles E.D. Black. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1893. https://archive.org/details/rivalpowersincen00popouoft/page/n7/mode/2up.

Rawlinson, Henry. England and Russia in the East. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970.

Sergeev, Evgeny. The Great Game 1856-1907: Russo-British Relations in Central and East Asia. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013.

Seton-Watson, R.W. Disraeli, Gladstone & the Eastern Question. Hoboken: Routledge, 2012. E-Book.

Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Thomsen, David. Europe Since Napoleon. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1963.

[1] Lawrence Freedman, “Stephen Pinker and the long peace: alliance, deterrence and decline,” Cold War History 14, no. 4 (2014): 657, https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2014.950243.

[2] Freedman, “Stephen Pinker”, 664.

[3] Freedman, 664.

[4] Henry Rawlinson, England and Russia in the East (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 189.

[5] George N. Curzon, Russia in Central Asia in 1889 and the Anglo-Russian Question (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1889), xii.

[6] Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia (New York: Kodansha Globe, 1994), 2.

[7] Evgeny Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907: Russo-British Relations in Central and East Asia (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013), 19.

[8] Dilip Kumar Ghose, England and Afghanistan: A Phase in Their Relations (Calcutta: The World Press Private Ltd, 1960), 4.

[9] Rawlinson, England and Russia, 365.

[10] K.W.B. Middleton, Britain and Russia: An Historical Essay (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1971), 49.

[11] J.A.R. Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations 1689-1943 (London: Methuen & Co., 1944), 122.

[12] Hopkirk, The Great Game, 360.

[13] David Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1963), 232.

[14] Lord Cromer, Essays, 275, quoted in Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 90.

[15] A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 83-85.

[16] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 60-61.

[17] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 97.

[18] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 227.

[19] Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 85.

[20] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 97.

[21] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 226.

[22] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 61.

[23] Middleton, 61.

[24] Rawlinson, England and Russia, 339.

[25] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 158.

[26] John Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs 1815-1885: Europe and Overseas (London: Routledge, 1998.), e-book, 70.

[27] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 69-70.

[28] Charles Marvin, The Russians at the Gates of Herat, quoted in Hopkirk, The Great Game, 419.

[29] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 72.

[30] Richard Aldous, The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone vs. Disraeli (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), 276.

[31] R.W. Seton-Watson, Disraeli, Gladstone & the Eastern Question (Hoboken: Routledge, 2012), e-book, 552.

[32] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 72.

[33] Hopkirk, The Great Game, 359.

[34] Seton-Watson, Disraeli, 552.

[35] Seton-Watson, 555.

[36] Seton-Watson, 553.

[37] Queen Victoria to the Prince of Wales, quoted in Hopkirk, The Great Game, 379.

[38] Seton-Watson, Disraeli, 556.

[39] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 61.

[40] Hopkirk, The Great Game, 310-311.

[41] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 114.

[42] Hopkirk, The Great Game, 359.

[43] Hopkirk, 397-398.

[44] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 115.

[45] Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 229.

[46] Taylor, 229.

[47] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 481.

[48] Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 229.

[49] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 481.

[50] Zablochii, Kiselev, iii. 37, quoted in Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 91.

[51] Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 215.

[52] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 62.

[53] Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery, 215-216.

[54] Taylor, 216.

[55] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 122.

[56] Hopkirk, The Great Game, 360.

[57] Henry Havelock, ‘Constantinople and our Road to India’, quoted in Henry de Worms Pirbright, England’s Policy in the East (London: Chapman and Hall, 1877), 185, https://archive.org/details/englandspolicyi00pirbgoog/page/n6/mode/2up.

[58] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 124.

[59] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 65-66.

[60] William Ewart Gladstone, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1876), 31, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bulgarian_Horrors_and_the_Question_of_th/ipQDAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover.

[61] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 429-430.

[62] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 67.

[63] Middleton, 67.

[64] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 127.

[65] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 67.

[66] Middleton, 68.

[67] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 140.

[68] Marriott, 141.

[69] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 69.

[70] Thomsen, Europe Since Napoleon, 433.

[71] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 70.

[72] Alexis Sidney Krausse, Russia in Asia: A Record and a Study, 1558-1899 (Leiden: Global Oriental, 2012), e-book, 306.

[73] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, xiv-xvi.

[74] Sergeev, 145.

[75] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 77.

[76] Curzon, Russia in Central Asia, 34-37.

[77] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 72.

[78] Józef Popowski, The Rival Powers in Central Asia or The Struggle Between England and Russia in the East, trans. Arthur Baring, ed. Charles E.D. Black (Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1893), 171-172, https://archive.org/details/rivalpowersincen00popouoft/page/n7/mode/2up.

[79] Curzon, Russia in Central Asia, 277.

[80] Edward Cazalet, England’s Policy in the East: Our Relations with Russia and the Future of Syria (London: E. Stanford, 1879), 18, quoted in Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 153.

[81] Rawlinson, England and Russia, 339.

[82] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 57-58.

[83] Sergeev, 58.

[84] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 77.

[85] George N. Curzon, Frontiers (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1907), 40-41, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433082424254&view=1up&seq=9.

[86] G.B. Malleson, The Russo-Afghan Question and the Invasion of India (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1885), 66, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t9v12007h&view=1up&seq=7.

[87] Gorchakov to Brunnov correspondence, Saint Petersburg, March 7, 1869, quoted in Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 127-128.

[88] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 130-131.

[89] Lowe, Britain and Foreign Affairs, 77.

[90] Rawlinson, England and Russia, 365.

[91] Curzon, Russia in Central Asia, 358.

[92] Curzon, Frontiers, 19.

[93] Curzon, Frontiers, 19.

[94] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 72-73.

[95] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 138-139.

[96] Marriott, 138.

[97] Middleton, Britain and Russia, 73.

[98] Marriott, Anglo-Russian Relations, 139.

[99] Sergeev, The Great Game 1856-1907, 209.

[100] Correspondence of Dondukov-Korsakov, 1884, quoted in Sergeev, 201.

[101] Curzon, Russia in Central Asia, 321.

[102] George Cawston and Edward Stanford Ltd., The Eastern Question in Europe and Asia, 1886, map on linen, 42 cm x 68 cm (16.54 in x 26.77 in), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7420.ct003773.

[103] G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co., Central Asia: Afghanistan and her relation to British and Russian territories, 1885, map, 45 cm x 77 cm (17.72 in x 30.32 in), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7210.ct001160.

[104] John Bartholomew & Company, Changes in Turkey in Europe 1856 to 1878, 1912 map, dimensions unknown, Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA, https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/balkans_1912.jpg

[105] W.H. Payne, Letts’s Bird’s Eye View of the Approaches to India, 1900, map, 49 cm x 72 cm (19.29 in x 28.35 in), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., USA, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7631a.ct002013.