“Rule, Britannia!”

The Union of Foreign and Domestic Politics in Mid-Eighteenth Century Britain

Introduction

“Rule, Britannia, rule the waves; Britons never will be slaves.”[1] This verse, from the poem “Rule, Britannia” by the Scot James Thomson, has had immense resonance for Britons throughout the past two and a half centuries, yet the poem was never more relevant than when it was initially written and popularized in the mid-eighteenth century. With the help of music composed by Englishman Thomas Arne, this new patriotic song promoting British maritime destiny became widely beloved almost immediately after its public debut in 1745 (it premiered to a royal audience five years earlier). What about this tune so instantly enthralled the British public? More than any other jingoistic anthem, “Rule, Britannia” captured the zeitgeist of this turbulent time; feelings of British exceptionalism in the areas of personal liberties, political freedom, and mercantile economics, as well as antagonism towards the absolutist monarchies of the Continent, were running high within the populace. The lyrics of this song depict, with accuracy and rhetorical flourish, the feelings of the era from 1740 through 1760, particularly the intimate connection between foreign and domestic affairs.

Thomson’s word choice is critical, especially in the chorus of the song, which was quoted above. In said chorus, Thomson exhorts Britannia to “rule the waves”, as well as mentioning that “Britons never will be slaves”[2]; this wording depicts the tenuous nature of the times, as the eventual British dominance of the seas and the security of her people were not guaranteed in 1740. The author has a clear concept of the connection between naval supremacy and political and economic liberty, setting Britain in contrast with the absolutist powers, namely France, who would deny her both. These themes of interconnectedness and the special role of Britain and her people are echoed in many of the poem’s later stanzas. In the second verse, Thomson writes: “The nations, not so blest as thee, Must in their turns to tyrants fall; While thou shalt flourish great and free, The dread and envy of them all.”[3] This describes contemporary British attitudes with respect to the importance of their political liberty and constitutional monarchy. By comparing other nations with their absolute monarchies to the freedom of Britain after the Glorious Revolution, Thomson shows how distinct the island is; all other nations, mainly on the Continent, are “not so blest as thee” and thus “dread and envy”[4] the British system. In the fifth stanza, Thomson pens the words: “To thee belongs the rural reign; Thy cities shall with commerce shine; All thine shall be the subject main, And every shore it circles thine.”[5] This set of lyrics brings up the economic power of Britain and its quest for colonial possessions to expand its mercantile empire. This power is based both in rural and urban settings, but chiefly in the joint operation of the two, as rural and colonial products supplied and were exported from the cities. The economic power of the island nation is tied back to naval ascendancy in the second half of the verse, “All thine shall be the subject main, And every shore it circles thine.”[6]; the ‘main’ in this case was the oceanic realm, which would be controlled by the British, along with all of the coasts bordering thereon. These aspirations of colonial and economic hegemony would resound throughout the mid-eighteenth century.

“Rule, Britannia” would not be nearly as renowned if its lyrics were not so resonant with the population of the Empire at the time it debuted. Thomson’s words set the stage for what may have been the most transformational era in British history to that point, and the sentiments expressed in his poem would echo throughout the period. This paper will argue that those sentiments – the entangled nature of domestic and foreign affairs, as well as economic and colonial aspirations – were the main themes of the twenty years after 1740. Before delving into the evidence for this contention, the general political landscape of the age needs to be understood.

The Political Landscape of the Mid-Eighteenth Century

It is difficult to appreciate the indistinguishability of domestic and foreign politics during the mid-eighteenth century without proper context. Two major aspects of the age differentiate it from the periods coming before and after it: the character of domestic politics and the function of the state.

The Character of Domestic Politics

Domestic politics in the period from 1740 to 1760 were typified by two important trends: the ascendancy of the Whig party and the importance of the patronage system.

The Era of Whig Supremacy

The first aspect of domestic politics that must be grasped is that the traditional political dichotomy of the previous decades, with Whigs and Tories in a shifting balance, was no longer operative; it was succeeded by an era of near total Whig domination under men like Henry Pelham, William Pitt the Elder, and the Duke of Newcastle. The decline of the Tory party was slow and steady, starting with the failed Jacobite uprising in 1715; afterwards “one-party monopoly of all central offices of government and Household and one-party control of the main institutions of county administration remained unbroken until the death of George II”[7] in 1760. The Tories were relegated to backbencher status, steadily losing influence and seats in the Commons; of the six-hundred-odd places in Parliament, the number of Tory MPs declined from about one-hundred-forty to fewer than one-hundred-twenty over the period from 1742 to 1747.[8] Tories remained a pole of politics, but were largely outcast and relegated to the margins of domestic affairs. The fracturing of the Tory party led to a series of Whig-dominated governments in the mid-eighteenth century, which altered the character of domestic politics.

The partisan divides that mattered in this era were between the ‘Old Corps’ Whigs, seen as the establishment, and the ‘new’ or ‘Patriot’ Whigs, who were viewed as the opposition and who would work with Tories when their interests aligned. The Old Corps is often represented by the Pelhams, Henry and his brother Thomas, the Duke of Newcastle, while the Patriot faction counted a revolving cast of leaders, including William Pitt the Elder and Henry Fox. The Old Corps, representative of the landed aristocracy, defended three principles: “moderate Whiggism, service to the crown and personal loyalty to the acknowledged leaders of the Whig party.”[9] The new Whigs, in contrast, represented the interventionist, pro-colonial, merchant interest and were able, through the incredible oratory of Pitt, to gain popular support via the press. This faction (along with some Tories) latched on to what was alternately known as the “reversionary interest”[10] and Leicester House: the group led by Frederick, Prince of Wales, and, after his death, the Dowager Princess and her son, the future George III. The Hanoverian monarchs were infamous for their internecine hatreds – Churchill would contend that “It was the Hanoverian family tradition that father and son should be on the worst of terms”[11] – and politics came to revolve partially around the conflict between King George II and his potential successors. Leicester House set up what was in essence a ‘shadow’ Court, allowing opposition MPs to show fealty to the dynasty while also challenging regime policy.[12] Still, policy differences were minor compared to the dynastic conflicts of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, as the Hanoverian succession was accepted and religious issues were on the back-burner.

The governments of this period were generally controlled by the establishment Old Corps, but there were frequently places found for new men like Pitt and Fox. Leaders of the Parliamentary opposition did not seek to overturn the government wholesale, but instead to gain “places for themselves and some of their friends,”[13] which rendered their opposition status as legitimate in the eyes of political society. The so-called ‘broad-bottom’ administrations brought about when opposition Whigs joined the Old Corps were some of the most successful of the period, especially the Pitt-Newcastle ministry of 1757 through 1761. Over time, the appointing of Patriot figures into government positions reduced the number of strictly opposition Whig MPs; in 1741 there were one-hundred-thirty-one opposition Whigs, which decreased to ninety-seven in the 1747 election and bottomed out at forty-two MPs in 1754.[14] These former rivals were integrated into the establishment through the judicious use of another key factor in mid-eighteenth-century politics: patronage.

Patronage and Corruption

Mid-eighteenth-century politics in Britain were defined less by a modern conception of representative democracy than by influence, patronage, and, some may claim, corruption. Due to the unique structure of government with respect to voting and representation, much of Parliamentary politics at this time focused on prestige and personal advancement. As the eminent scholar of political action in this era, Lewis Namier, cleverly stated, men “no more dreamt of a seat in the House [of Commons] in order to benefit humanity than a child dreams of a birthday cake that others may eat it”[15]; this contention has been debated in more recent scholarship.

Before diving into the details of how patronage operated within the political system, it is necessary to define the term. Patronage, otherwise known as influence, was essentially the granting of monetary or other considerations for either a seat in the Commons or support for the sitting government. Patronage could be dispensed by the government, the monarch or other royals, or even private individuals who controlled boroughs and thus seats in Parliament. The granting of titles, offices, sinecures, and pensions was often the sweetener in these deals to lock in the support of certain MPs or factions in the Commons. That is not to say that the shrewd dispensation of influence, royal or otherwise, guaranteed stable government and support of a majority in Parliament; even the sharpest patrons of the day, Newcastle and Robert Walpole, were turned out of their ministries over time.[16] MPs and those who wished to join Parliament were receptive to this system; only a relative few in the opposition thought of patronage as corrupt per se, as “the need for some such form of constitutional lubricant was generally recognized by impartial observers”.[17] At the time, MPs were not paid salaries, leading to greater interest in recouping the sometimes high costs of initial election and maintenance of a dwelling in London.[18] Regardless, joining Parliament was the goal for most young aristocrats and the words of Lord Chesterfield to his son could be seen as a motto for these men: “’You must make a figure there if you would make a figure in your country.’”[19] Chesterfield’s words had a double meaning; ‘making a figure’ could refer to either earning a sum of money or a lucrative office, or alternatively, creating a broader impression on people and making a name for oneself in politics.

Parliament was the preferred destination for British elites and thus revolved around the interests of the landed aristocracy. The seemingly venal concerns of politics at the time may lead modern observers to call the system corrupt, yet many of the most important disbursers of patronage spent immense private sums on elections. Henry Pelham died a poor man, despite being in positions of financial power for over thirty years, and his brother Thomas, Duke of Newcastle, spent more than £300,000 of his personal wealth on supporting the Whig government[20]; William Pitt “ostentatiously refused to take a penny beyond his official salary as Paymaster-General,”[21] which could become a profitable office if one wished to make it so. Just as significant as the structure of national politics is the purpose thereof.

The Purpose of Politics and the Function of the State

The purpose of the state in the mid-eighteenth century was far different than the modern conception of what the function of government should be. This distinction is clearly seen through a variety of prisms: the separation of local and national issues, the definition of what constituted a truly national matter, and the critical status of colonial possessions in governance.

First, local matters were plainly divided from national ones; much of what modern observers would consider of national importance was seen as either a private matter or something to be dealt with locally. Poverty, criminality, and transportation, for example, were problems which were most visible on a local level and were handled there. Far more Britons interacted with their resident Poor Law commissioner or Justice of the Peace than with the MP who supposedly represented their interests in the Commons. These officers were taken less from the landed aristocracy and more from the so-called ‘middling sort’, minor gentry, wealthy merchants, and other local notables.[22] Most Britons did not see nation-level politics as important to daily life unless and until war broke out.

Truly national issues were few and far between, but one such issue to which all Britons paid attention was warfare. Of the twenty years from 1740 to 1760, Britain was in military conflict for all but four[23], leading to martial affairs taking on greater importance. Wars could only be conducted on a national scale, with regiments for the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War being drawn from England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and the North American colonies. The armed forces grew meaningfully, with about five percent of all men of military age serving full-time during the Austrian war and nearly ten percent of that same group during the Seven Years’ War; this broadened the horizons of those serving and tended to increase patriotic fellow-feeling.[24] Parliament also included many military office-holders, exemplifying the significance of armed conflict to the national government; during the course of the Seven Years’ War the number of MPs who were officially in the armed services increased considerably. In 1761, for example, sixty-four army officers were elected[25] and twenty-one naval officers were returned[26], including many of the highest-ranking and most successful leaders of the Seven Years’ War. The fact that so many military officers sat in Parliament was representative of the import of warfare as a function of the state.

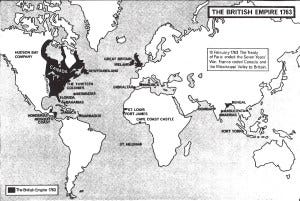

Finally, the intense focus on colonial issues – expansion, protection, and economics – is an aspect of the mid-eighteenth century that is completely alien to modern observers. The fact of great power competition on the colonial stage would drive much of the conflict endemic to this age. It is also representative of the entanglement of national and foreign concerns; should colonies, though located abroad, be primarily seen as ‘domestic’? Prosperous colonies were perceived as the key to a stable society and a growing economy, and the metropole’s interests lied in protecting colonial trade and the colonists themselves.[27] National politicians, although content to leave local governance to others, were deeply concerned with directing Imperial and commercial policies.[28] Mercantilist economic thought, which dominated the period, placed a major premium on developing and controlling colonial trade, especially in gaining raw materials and natural resources from colonies in exchange for manufactured goods. The competition over colonial possessions around the world led to the two major wars of the age and drove British foreign policy on the Continent.

Colonial and Continental Conflicts

The story of the period between 1740 and 1760 was one of tensions between Britain and the absolutist monarchies of Continental Europe, chiefly Bourbon France. The three major interests undergirding this existential conflict were economics and trade, colonial protection and expansion, and the preservation and defense of the Hanoverian dynasty. Throughout the period, the concerns of two major factions dominated British politics: the mercantilist economic elite and the reigning monarch, King George II. The issues they were most worried about exemplify the Gordian Knot that bound together foreign and domestic subjects. Economic elites cared most about promotion of trade, colonial expansion, and mercantilist conflict with other powers, while the monarchy focused on balancing the interests of its German possessions with dynastic matters in Great Britain. Both factions opposed Continental absolutism and its colonial manifestations, which allowed for a degree of unity where there may otherwise have been strife. The concerns of these two blocs typify the tangled web of domestic and foreign politics in the twenty years after 1740.

Economic and Mercantile Elites

The political activity of the financial elite and merchant class of the mid-eighteenth century was mainly driven by concerns over trade and colonies, issues which, in an age of mercantilism, were inextricably linked. The influence of trade interests can be found in many of major decisions that were taken by the British government in this era, especially those in the realm of war and international conflict. These interests had two significant impacts on politics, both of which combine domestic and foreign concerns. First, mercantile theories on economics were ascendant and largely controlled how international trade and colonial policy were formulated. Next, the structure of state finance developed greater complexity and became more entwined with private commercial interests, particularly in the City of London.

Mercantilist Colonial and Economic Thought

Mercantilism – an economic theory focused on building and controlling a closed system of trade within a commercial empire, exploiting natural resources in colonial territories, and competing aggressively with other economic powers – reigned supreme among the politicians and commercial interests of the day. Mercantilists saw the world economic ‘pie’ as fixed, in that they believed there was a given level of prosperity and natural bounty that had to be divided between powers; there was no conception of expanding the ‘pie’ through innovation or financialization, as there is in more modern economic theory. This system led to rapid expansion of colonial trade, the start of two major international wars, and enhanced levels of commercial competition.

Colonial trade and the extraction of natural resources were the centerpieces of mercantilist dogma in this period, and they were pursued with vigor by the British. Britain’s colonies in North America, the West Indies, Africa, and India were replete with resources that the home islands lacked. In North America, timber, furs, and fish were abundant, while the West Indies produced popular commodities like sugar and coffee. Slave labor, the main export from African colonies, was crucial for the plantation economy of the Caribbean. In Asia, luxuries abounded, with trade in exotic spices and tea from India and silks from China. Overall overseas trade jumped two-hundred-fifty percent from the first decade of the eighteenth century to the ten years ending in 1774.[29] Colonial trade expanded even faster than foreign commerce; British imports from her colonies increased seventy-five percent over a period in which European imports declined more than ten percent.[30] Consistent with the mercantile system, a good deal of the colonial imports to Britain were then re-exported for the profit of home island merchants; this accounted for at least forty percent of British exports in the 1750s.[31]

Mercantilist economies needed to exert total control over these resources and the trading thereof to maximize the nation’s profits. Thus, laws relating to navigation and the carrying of goods became widespread; British goods, from colonies or metropole, had to be carried by British-flagged vessels, keeping the closed loop intact and cutting out rivals.[32] This led to a drastic rise in the tonnage of Britain’s merchant marine, which tripled from “3,300 vessels (260,000 tons) in 1702 to 9,400 vessels (695,000 tons) in 1776”.[33] These restrictions were not eased in wartime; on the contrary, they often were expanded and enforced more vigorously. In 1756, at the official outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, Britain adopted a policy of “dubious legality—the ‘Rule of the War’ . . . which declared that neutrals could not benefit from trade privileges extended by a belligerent Power during a time of war.”[34] These trade limitations evince the mercantilist drive for complete resource and colonial domination.

That drive led directly to British involvement in the two major wars of the period, and caused significant violent conflict even during nominal peacetime. Britain’s part in what would become the War of the Austrian Succession began in 1739 with a conflict known as the War of Jenkins’ Ear. This initial fight against the Spanish was relegated entirely to the seas and islands of the West Indies before metastasizing into a broader European war focused on Austrian possessions. The dispute began with repeated Spanish boarding and seizure of British commercial vessels in the West Indies and the South Sea, areas that a mercantilist Spain claimed exclusive economic rights over. British popular opinion was inflamed by sordid tales of Spanish atrocities, and war erupted late in the year with the raids of Vice-Admiral Vernon in the Caribbean. In the minds of Britons, the conflict “was widely viewed as a war purely for commercial gain: at the declaration, stocks rose.”[35]

Similar undercurrents were at play in the buildup to the more consequential confrontation for Britain in this period, the Seven Years’ War. In this instance, the colonial and commercial threat was in North America and came from Britain’s most dangerous enemy: France. The leading government men overseeing North American colonial affairs at the time, the Duke of Newcastle and the Earl of Halifax, were extremely wary of the “openly aggressive actions begun by the governors of New France after 1748”.[36] Halifax was the head of the Board of Trade, which regulated commerce and therefore dealt most directly with colonial issues; the fact that the colonies were overseen by the Board of Trade demonstrates the linkage between economic and colonial interests. Halifax saw the increased French penetration into the Ohio Valley and the Nova Scotia region as an effort to “wall in the British provinces” and take control of the lucrative resources and Indian trade beyond the new frontier.[37] In response, orders were sent “to all American governors ‘to prevent, by Force, These and any such attempts that may be made by the French, or by the Indians in the French interest’.”[38] These orders were carried out, leading to the opening conflicts of the Seven Years’ War at Forts Duquesne and Necessity.[39] The commercial and colonial underpinnings of the conflict were clear based on the prime targets of later attacks: trading posts, fortresses, naval stations, and resource-producing islands.

In both of these wars, support from the commercial class was significant, particularly in antagonism to the economic might of France. The French were seen as the preeminent state on the Continent and their commercial prominence challenged British interests. The two nations competed across the globe for resources and riches, but France was often “able to undersell British goods in foreign markets.”[40] Merchants and concerned citizens founded the Anti-Gallican Association in 1745 to encourage consumer purchases of British manufactures and discourage French imports.[41] The attitude that drove that organization was still commonplace a decade later; a 1756 anonymous pamphlet claimed “that the Inundation of French Luxuries which has of late Years poured in so rapidly upon us, has done us more Hurt than French Arms or French Politicks.”[42] This widespread understanding of the impact of trade and competition with France allowed for a national focus on winning economic and military conflict at all costs.

State Finance and Private Interests

One issue of paramount importance to Britain during the mid-eighteenth century was the ability for the state to raise large amounts of capital to fight the major wars that it undertook. These wars, as depicted earlier, were fought for mercantile objectives and gleaned heavy support from the commercial class. This backing did not only come rhetorically, but was substantiated with loans and hard currency. In this era, the state and private financial interests were in a symbiotic relationship in which the government had to rely on private financiers and bankers to underwrite the massive loans required to fight global wars. The financiers made money on the resale of British securities and lent money to the state at rates that were unheard of on the Continent, providing a boon to both sides of the transaction.

During the War of the Austrian Succession and especially the Seven Years’ War, funds for military use were raised via the City of London, the Bank of England, and a variety of public subscription schemes, including lotteries and discount annuities. Britain’s ability to raise funds via taxes on its citizens was adequate for peacetime, but was not nearly robust enough to cover the unprecedented costs of these conflicts; the land tax, malt duties, and sinking fund fell far short in paying for the massive increase in troop strength that was necessary.[43] To regularize these tax receipts, which would come in sporadically throughout the year, the government borrowed from the Bank of England against expected revenues on a short-term basis. In the early 1750s, a time of nominal peace, the interest rates granted by the Bank to the state were as low as three percent, “the lowest level the rate ever reached in the eighteenth century.”[44] Wartime borrowing was slightly different, in that it involved more negotiation respecting rates and amounts to be lent; still, short-term rates remained low throughout the Seven Years’ War and only rose to three-and-a-half percent at the height of the conflict.[45] This is only part of the picture, however, as the maximum attainable tax revenues that could be raised by the state were reached quickly and long-term borrowing was necessary to cover the rapidly increasing costs of the war. For example, the cost of government in 1754, at the start of the Seven Years’ War, was a mere £2,500,000 compared with the almost inconceivable £19,100,000 required in 1761[46]; the tax base simply could not be exploited to the degree necessary to return the desired funds. These new constraints made financial innovation not only possible, but mandatory; the accompanying rise in investor confidence in the government’s ability to repay its debts allowed the British to outraise all of its Continental rivals and propelled the next century of industrial growth. The close relationship between public and private finance became even more intimate, as private interests worked with the state to underwrite its debt and create funding mechanisms to entice the general public to subscribe to the debt offerings. Keeping the nominal rate of interest low was important to the government and the financiers, as it allowed for Britain to appear to be a bulwark of capital security during the wars and did not harm the valuation of earlier, lower interest debt offerings (many of which were held by these commercial interests themselves).[47] As the stated rate needed to remain stable, sweeteners, known as “douceurs”, were added to the offerings; these included lottery schemes, in which purchasers gambled on a higher return, and discounted annuities, where buyers received “stock with a total face value in excess of the amount he paid in to the Treasury.”[48] The power of private financial interests was exhibited in the government funding process, but also was seen in more practical politics.

The City of London, the trading center of British life, dominated commerce in the Empire. It handled three-quarters of the nation’s trade[49], and as described, controlled government fundraising during wartime. These realities gave the City and the merchant interests that guided it a significant level of political power, even though they directly controlled relatively few Parliamentary seats. Their political ideology can be fairly summed up with a quote from Lord Holderness:

I am convinced you will agree with me in one principle, that we must be merchants while we are soldiers, that our trade depends upon a proper exertion of our maritime strength; that trade and maritime force depend upon each other, and that the riches which are the true resources of this country depend upon its commerce.[50]

These mercantile interests found a champion for their ideology in the ‘Great Commoner’, William Pitt the Elder. Pitt’s ‘blue water’ strategy, focused on naval warfare and capturing trade while deprioritizing Continental combat, was exactly what the City was looking for.[51] Pitt was moved into government service as Paymaster of the Forces in 1746 and further solidified public opinion in his favor when he refused to take the typical emoluments that went with that lucrative office.[52] The love affair with Pitt continued, even when he was again out of government, and it was largely the City interests, the public presses which they influenced, and the middling classes who were involved in commerce that pushed him back into power in 1757.[53] After Pitt’s brief tenure at the head of a ministry with the Duke of Devonshire, he was dismissed by the King and subsequently gained support from the nation, as “The great towns sent the freedom of their cities to Pitt, and, in the famous phrase of Horace Walpole, ‘for some weeks it rained gold boxes.’”[54] This allowed Pitt to dictate his terms, start a new ministry with Newcastle, and successfully conduct the Seven Years’ War from 1757 through 1761; the political power of the City interests was clear.

King George II and Hanover

Another faction that represented the commingling of foreign and domestic politics was the monarchy itself. King George II was the crowned ruler of Great Britain, Ireland, and the colonies, but he also had a direct connection to continental Europe – George II was the Elector of Hanover, a German state which had been held in personal union with the British crown since the accession of George I in 1714. The issue of Hanover was critical to both foreign and domestic politics throughout the mid-eighteenth century, and hit the peak of its relevancy during the wars of this period. The many problems which arose from the personal union were exacerbated by King George II’s preference for the Electorate over the Empire. According to Churchill, George’s “hereditary Electorate of Hanover was dearer to his heart than the Kingdom of Great Britain.”[55] The monarch’s German identity was important to him, and he showed it; George spent most summers in Hanover and preferred ministers, like Lord Carteret, who spoke his native German. He also traveled to the Electorate to defend it in wartime, becoming the last British King to lead troops in battle at Dettingen in Bavaria in 1743. Unfortunately for Britain, its enemies knew that George valued Hanover as well; the French in particular would frequently threaten German campaigns as leverage over the British.[56] Chiefly due to George’s personal preference, the protection of Hanover became a cornerstone of British foreign policy on the Continent.

Both of the wars of the mid-eighteenth century deeply involved Hanoverian concerns and included combat within and around the Electorate itself; European alliances were built and discarded based on who could best ensure the safety of George’s German territories. Ministers and ministries rose and fell on the back on their attitudes towards Hanover as well; George’s fondness for Carteret and Walpole was at least partially due to their pro-Hanoverian leanings. On the other hand, George’s antipathy for William Pitt was entirely founded on the Great Commoner’s dislike for German interests. Pitt was obviously one of the ablest administrators, orators, and public personas of the day, yet he was excluded from government for most of the mid-eighteenth century; when he was first made a minister, he was given the profitable yet mostly unimportant position of Paymaster of the Forces. The shunning of Pitt was due to a particular speech he made in the House of Commons in 1742 opposing the British payment of Hanoverian troops during the War of the Austrian Succession; the words that set the King firmly in his resentment were:

It is now too apparent, Sir, that this great, this powerful, this mighty nation, is considered only as a province to a despicable Electorate; and that in consequence of a scheme formed long ago, and invariably pursued, these troops are hired only to drain this unhappy country of its money. That they have hitherto been of no use to Great Britain or to Austria, is evident beyond a doubt; and therefore it is plain that they are retained only for the purposes of Hanover.[57]

Despite the venom, Pitt did change his mind on the Hanoverian issue, eventually believing that the war for the colonies would be won in Europe[58]; this gave George II reason to let Pitt lead a ministry, resulting in the incredible highs of the Seven Years’ War.

Alliances and military decisions were driven by Hanoverian concerns as well; this was evident in one of the biggest costs of waging war: the subsidies for European forces. British Continental policy during the mid-eighteenth century revolved around paying foreign troops to fight in Europe and, as much as possible, avoiding the deployment of British manpower on the Continent. Subsidies were used in both peacetime and during conflict, and were unpopular nearly always; Pitt’s withering speech in 1742 was rallying against subsidies for Hanoverian troops. Wartime subsidies, although painful and expensive – most of the money borrowed by the government ended up being sent to other European states – were at least justifiable; payments to secure Hanover outside of war were seen as wasteful since “peacetime allies could not be depended upon to be wartime allies”[59]. Indeed, the Duke of Newcastle had to concoct a plan to influence the Imperial Election for King of the Romans by paying German states so as to avoid the constraints on Newcastle’s ability to provide regular subsidies during the interwar period.[60] These peacetime maneuvers led to the most radical shift in alliances in the whole of the eighteenth century – the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 in which the Habsburgs and Bourbons exchanged their eternal enmity for amity – and the subsequent outbreak of the Seven Years’ War. Wartime subsidies were granted to a wide variety of European states during this period, from large nations like Austria, Russia, and Prussia to smaller states like Hanover and Hesse. In the rare cases when British troops would be sent into Continental conflict, they were often either joined by German allies, including the Hanoverians, or led by German commanders, notably Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. When Britons served with Hanoverians, many came away with positive impressions; one officer said, after the 1745 Battle of Fontenoy, “’by the Behaviour of the Hanoverians they may henceforth Justly be Stild of the same Nation.’”[61]

British attitudes towards Hanoverian troops were very different when the Germans were serving as protective mercenary units on home soil, however. The major reaction to the use of foreigners as guardians of Britain was negative[62], as there was a long-held suspicion of standing armies; regardless, Germans had been used for defense of the homeland since the early 1700s.[63] At a time of crisis, this was seen as a significant weakness for Great Britain. Still, the alternative of training a national militia was controversial given the violent culmination of the disputes over those forces during the time of Charles I.[64] William Pitt was a major proponent of the Militia Act, which would ensure that defense of the Isles was carried out by British militiamen, but it was unable to pass until tensions with the Hanoverian mercenaries reached a breaking point. Popular sentiment was avowedly against the use of mercenaries; a cartoon espousing this message had the following verse: “Oh! Shame to Nature, Shame to Common Sense; Must Britain for it’s own Defence, Depend on Champions not her own, so weak She cannot Stand alone; Not so, Unchain her willing hands, And we’ve no need of foreign Bands.”[65] Finally, in 1757, the Act passed; this was only possible with the support of formerly reticent Whigs who wanted the Hanoverian soldiers stationed back on the Continent, while remaining in British pay – the Tories were longstanding supporters of a strong national militia and voted for the Act.[66] This compromise, allowing for British militias while retaining the Hanoverian mercenaries in British pay in Europe, embodied the linkages between domestic and foreign politics and policies.

Conclusion

“Thee haughty tyrants ne’er shall tame; All their attempts to bend thee down, Will but arouse thy generous flame, But work their woe and thy renown.”[67] These lyrics, from “Rule, Britannia”, get to the heart of the political issues of the period from 1740 to 1760; great power competition between Britain and her absolutist rival, France, dominated the age, but the British people firmly believed in their supremacy. The question of whether domestic or foreign politics were more important at this time is a false binary; national and international issues were one and the same in the mid-eighteenth century, largely driven by the preeminence of colonial, economic, and dynastic concerns. This intersection of the domestic and the foreign is seen consistently, particularly during the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. The fight against Continental absolutism, the importance of economic affairs and colonial expansion, the forging of British power and identity through warfare, and the issue of Hanover all combined to create a tangled web of interrelated interests, of which the categories ‘domestic’ and ‘foreign’ cannot separately apply. The stanza from “Rule, Britannia” which best sums up this period is a stark rendering of the belief that British political liberties, economic freedoms, and commercial and military might will always be ascendant over absolutist, reactionary Continental powers: “Still more majestic shalt thou rise, More dreadful from each foreign stroke; As the loud blast that tears the skies, Serves but to root thy native oak.”[68]

Bibliography

An address to the great. Recommending better ways and means of raising the necessary supplies than lotteries or taxes. With a word or two concerning an invasion. London: printed for R. Baldwin, at the Rose in Paternoster Row, 1756. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (accessed December 7, 2019). http://tinyurl.gale.com/tinyurl/CTTNk1.

Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of the Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Browning, Reed. “The Duke of Newcastle and the Financing of the Seven Years’ War.” The Journal of Economic History 31, no. 2 (June 1971): 344-377. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117049 .

Browning, Reed. “The Duke of Newcastle and the Imperial Election Plan, 1749-1754.” Journal of British Studies 7, no. 1 (November 1967): 28-47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/175379 .

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: The Age of Revolution. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1967.

Clayton, T.R. “The Duke of Newcastle, the Earl of Halifax, and the American Origins of the Seven Years’ War.” The Historical Journal 24, no. 3 (September 1981): 571-603. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2638884 .

Conway, Stephen. “War and National Identity in the Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Isles.” English Historical Review, September 2001: 863-893. DOI: 0013-S266/01/2647/0863 .

Green, Walford Davis. William Pitt, Earl of Chatham. New York: Fred DeFau and Company, 1900.

Holmes, Geoffrey, and Daniel Szechi. The Age of Oligarchy: Pre-industrial Britain 1722-1783. New York: Longman Publishing, 1993.

John, A.H. “War and the English Economy, 1700-1763.” The Economic History Review 7, no. 3 (1955): 329-344. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2591157 .

Namier, Lewis. The Structure of Politics At the Accession of George III. London: Macmillan, 1968.

O’Gorman, Frank. The Long Eighteenth Century: British Political and Social History 1688-1832. London: Arnold, 1997.

Owen, John B. The Eighteenth Century 1714-1815. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1976.

Pitt, William. The Speeches of the Right Honourable the Earl of Chatham in the Houses of Lords and Commons, With a Biographical Memoir and Introductions and Explanatory Notes to the Speeches. London: Aylott and Jones, 1848. Google Books (accessed December 7, 2019). https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=PC3IBcd8tsMC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP10 .

Schweizer, Karl. “The Duke of Newcastle and the Diplomatic Revolution, 1753-1757: A Historical Revision.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 28, no. 2 (2017): 167-194. DOI: 10.1080/09592296.2017.1309873 .

Scott, Hamish. The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815. Hoboken: Routledge, 2014. PDF.

Spector, Robert Donald. English Literary Periodicals and the Climate of Opinion During the Seven Year’s War. Studies in English Literature. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2015. PDF.

Thomson, James. “Rule Britannia by James Thomson.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45404/rule-britannia.

[1] James Thomson. “Rule Britannia by James Thomson.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45404/rule-britannia.

[2] Thomson. (emphasis added).

[3] Thomson.

[4] Thomson.

[5] Thomson.

[6] Thomson.

[7] Geoffrey Holmes and Daniel Szechi, The Age of Oligarchy: Pre-industrial Britain 1722-1783 (New York: Longman Publishing, 1993), 27.

[8] Frank O’Gorman, The Long Eighteenth Century: British Political and Social History 1688-1832 (London: Arnold, 1997), 142.

[9] Holmes and Szechi, The Age of Oligarchy, 269.

[10] Holmes and Szechi, 268.

[11] Winston S. Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: The Age of Revolution (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1967), 116.

[12] O’Gorman, The Long Eighteenth Century, 145.

[13] O’Gorman, 145.

[14] O’Gorman, 145-46.

[15] Lewis Namier, The Structure of Politics At the Accession of George III (London: Macmillan, 1968), 2.

[16] John B. Owen, The Eighteenth Century 1714-1815 (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1976), 100.

[17] Owen, 100.

[18] Owen, 103.

[19] Namier, The Structure of Politics, 1.

[20] Holmes and Szechi, The Age of Oligarchy, 269.

[21] Holmes and Szechi, 270.

[22] O’Gorman, The Long Eighteenth Century, 108.

[23] Those years were 1749 to 1753; even within this period where there was no declared war, there were unsanctioned clashes in the colonies, particularly in North America.

[24] Stephen Conway, “War and National Identity in the Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Isles,” English Historical Review, September 2001: 876. DOI: 0013-S266/01/2647/0863

[25] Namier, The Structure of Politics, 25.

[26] Namier, 31.

[27] Conway, “War and National Identity”, 891.

[28] O’Gorman, The Long Eighteenth Century, 176.

[29] O’Gorman, 177.

[30] O’Gorman, 177.

[31] O’Gorman 177-78.

[32] O’Gorman 23.

[33] O’Gorman 177.

[34] Karl Schweizer, “The Duke of Newcastle and the Diplomatic Revolution, 1753-1757: A Historical Revision,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 28, no. 2 (2017): 181, DOI: 10.1080/09592296.2017.1309873

[35] Hamish Scott, The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815 (Hoboken: Routledge, 2014), 44.

[36] T.R. Clayton, “The Duke of Newcastle, the Earl of Halifax, and the American Origins of the Seven Years’ War,” The Historical Journal 24, no. 3 (September 1981): 572, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2638884

[37] Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of the Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 36.

[38] Clayton, “American Origins of the Seven Years’ War,” 584.

[39] Clayton, 585.

[40] Conway, “War and National Identity”, 885.

[41] Conway, 885.

[42] An address to the great. Recommending better ways and means of raising the necessary supplies than lotteries or taxes. With a word or two concerning an invasion (London: printed for R. Baldwin, at the Rose in Paternoster Row, 1756) Eighteenth Century Collections Online. http://tinyurl.gale.com/tinyurl/CTTNk1.

[43] Reed Browning, “The Duke of Newcastle and the Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” The Journal of Economic History 31, no. 2 (June 1971): 345, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117049

[44] Browning, “The Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” 345.

[45] Browning, “The Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” 346.

[46] Browning, “The Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” 346.

[47] Browning, “The Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” 353.

[48] Browning, “The Financing of the Seven Years’ War,” 353.

[49] A.H. John, “War and the English Economy, 1700-1763,” The Economic History Review 7, no.3 (1955): 339, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2591157

[50] John, 339.

[51] Holmes and Szechi, The Age of Oligarchy, 262.

[52] Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, 135.

[53] Robert Donald Spector, English Literary Periodicals and the Climate of Opinion During the Seven Year’s War (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2015), 17-18.

[54] Walford Davis Green, William Pitt, Earl of Chatham (New York: Fred DeFau and Company, 1900), 100.

[55] Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, 126.

[56] Scott, The Birth of a Great Power System, 56.

[57] William Pitt, The Speeches of the Right Honourable the Earl of Chatham in the Houses of Lords and Commons, With a Biographical Memoir and Introductions and Explanatory Notes to the Speeches (London: Aylott and Jones, 1848), 38, Google Books (accessed December 7, 2019). https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=PC3IBcd8tsMC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP1038

[58] Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, 149.

[59] Reed Browning, “The Duke of Newcastle and the Imperial Election Plan, 1749-1754,” Journal of British Studies 7, no. 1 (November 1967): 32, https://www.jstor.org/stable/175379

[60] Browning, “The Imperial Election Plan,” 32-33.

[61] Conway, “War and National Identity,” 887.

[62] Conway, 889.

[63] Green, William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, 78.

[64] Green, 78.

[65] Conway, “War and National Identity,” 889.

[66] O’Gorman, The Long Eighteenth Century, 181.

[67] Thomson, “Rule, Britannia”.

[68] Thomson.